‘Parliament & Peterloo’

Exhibition in Westminster Hall between 4th July and 26th September 2019

THE Parliamentary Archives invites people to visit the ‘Parliament & Peterloo’ exhibition which opened on 4th July to mark next month’s 200th anniversary of the brutal state attack on unarmed workers and youth.

This free, small display explores the political and social background to the Peterloo massacre and Parliament’s reaction to it.

Researchers from Royal Holloway, University of London and the History of Parliament Trust contributed to the exhibition. They have discovered documents in the Parliamentary Archives relating to what happened at St Peter’s Field in Manchester on 16th August 1819.

Visitors can explore this material on an interactive table. Some of the documents were used as reference material for ‘Peterloo’, the 2018 feature film written and directed by Mike Leigh.

How can I visit and book tickets?

‘Parliament & Peterloo’ is open 9am to 6pm, Monday to Saturday, between 4 July and 26 September 2019 (except 26 August). Last entry is 5.30pm.

All visitors coming to Parliament during this period – to take a tour, watch debates and committees, or for other reasons – can see the exhibition.

A limited number of free tickets to visit the exhibition only can be booked online, by calling +44 (0)20 7219 4114 or in person from the Ticket Office at the front of Portcullis House on Victoria Embankment.

The display consists of panels outlining the background and aftermath of the murderous event.

After Waterloo

The defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 ended a war with France that had lasted almost 22 years. Britain emerged triumphant, but with massive debts and its economy ill-prepared for peace. Around 300,000 returning soldiers, many of them disabled, began to seek work. Orders for military supplies dried up, causing major upheavals in the industrial centres of the Midlands and North. In the countryside unprofitable land used to feed Britain during naval blockades was abandoned. Unemployment began to soar.

The Tory government led by Lord Liverpool tried to help British farming by taxing imports of cheaper foreign grain. The 1815 Corn Law benefited the landowning classes, but at the cost of keeping bread prices high and depressing the market for manufactured goods. In the same year the eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia created a dust cloud that caused catastrophic global crop failures. Working people in Britain began to starve.

Liberty and democracy

During the war the British state, fearing a French-style revolution, had clamped down hard on political protests. Campaigners seeking reforms were persecuted as unpatriotic French ‘Jacobins’. Meetings inciting rebellion or public protest were banned.

As the war ended, years of pent-up frustration with low wages and appalling living conditions boiled over. Rioting and ‘Luddite’ vandalism of industrial machinery became widespread. In 1816 Arthur Thistlewood attempted an armed uprising in London. In 1817 Parliament suspended Habeas Corpus, allowing the authorities to imprison people without charge.

The 1818 General Election showed how unrepresentative the political system was. For example in England less than 320,000 could vote for MPs out of a population of 10 million. With most women unable to meet property qualifications the English electorate represented 13% of adult males. In addition two-thirds of constituencies lacked opposition candidates in 1818 and did not experience a poll. Half of these were ‘rotten’ or ‘pocket’ boroughs controlled by a local aristocratic patron.

A satirical print is displayed ‘Consequences of a Successful French Invasion’ by James Gillray, 1798, showing French troops taking over Parliament and trashing Magna Carta and other rights documents.

In August 1819 the radical, Henry Hunt, was invited to Manchester which had no MPs, to take part in a mock election. The local magistrates banned the event after consulting with the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth.

A less provocative pro-parliamentary reform rally involving Hunt was planned for St Peter’s Field, Manchester, on 16th August. Local workers arrived in ‘contingents’ wearing their best clothes. Around 60,000 people assembled, including many women and children. Members of the Manchester Female Reform Society, led by Mary Fildes, escorted Hunt to the platform.

The magistrate William Hulton tried to break up the crowd by reading the Riot Act. He then ordered Hunt’s arrest. The inexperienced Manchester and Salford Yeomanry were summoned to help, but lost control of their horses. Fearing for their safety, Hulton ordered the 15th Hussars, a British army cavalry regiment, to charge and disperse the meeting. At least 18 were killed of whom 3 were women. About 700 were injured.

As well as a vivid centrepiece depiction of the massacre a sketch of the meeting of the Female Radical Reformers of Manchester, a satirical illustration from the Manchester Comet, 1822 (Chetham’s Library, Manchester), is displayed.

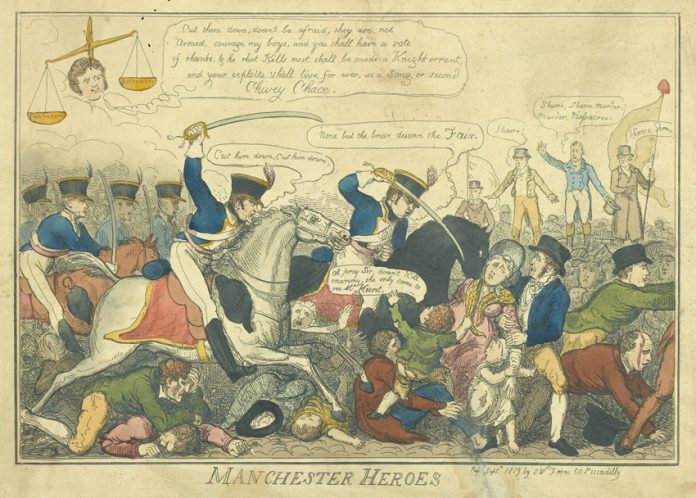

Also displayed is ‘Manchester Heroes’, the Peterloo Massacre 16 August 1819, a coloured etching by George Cruikshank, © Parliamentary Art Collection, WOA 3574. It conveys the ruthless brutality of the Hussars and the fearful fleeing protesters.

The aftermath

Public opinion was outraged. The press, mocking the memory of Waterloo, referred to the ‘Peterloo Massacre’. The government, however, supported the use of force and many of those involved were put on trial. Hunt was sentenced to two years in prison.

The ‘Six Acts’ passed by Parliament in 1819 banned all ‘unofficial’ large meetings. Magistrates were given extra powers to arrest people, and it became illegal to criticise the state in print.

The discovery of a plot to assassinate the Cabinet in 1820 seemed to justify the government’s actions, but a government spy had encouraged the plans. Five members of the Cato Street Conspiracy were found guilty of treason, including Arthur Thistlewood and William Davidson, a black Jamaican activist. They were executed outside Newgate Prison in front of vast crowds.

Parliament received many petitions concerning the events of 16th August and the subsequent legislation. Unsuccessful calls for an inquiry continued until at least 1832.

‘The Cato Street Conspirators’ is a print made by George Cruikshank. It was published by George Humphrey, in 1862. It is from the British Museum and shows the vicious nature of the British state.

Parliamentary reform

During the 1820s demands for change continued. Constitutional methods such as petitioning kept up the pressure on Parliament. Many of the laws discriminating against dissenters and Catholics were soon being discussed and modified. For many Tories this was too much and in 1830 the government collapsed and the Whigs came to power, headed by Lord Grey.

After a ferocious struggle, and riots in Bristol and Nottingham, the Great Reform Act of 1832 was passed. New voting qualifications increased the electorate to almost a fifth of adult males, although women were formally disenfranchised. In Lymington the first non-white MP, John Stewart, was elected.

Manchester now had its own MPs. Nearly 7,000 of its wealthier male householders and shopkeepers acquired the vote, a right not fully extended to all men in the United Kingdom until 1918. Some women over 30 were given the vote in 1918, but were only fully enfranchised in 1928.

Finally on display is An Act to amend the Representation of the People in England and Wales – The Great Reform Act of 1832.

The small display is timely and a reminder of Karl Marx’s and Lenin’s conclusions that the capitalist state cannot be reformed.

It is an instrument of the capitalist class to suppress the working class and must be overthrown, smashed and replaced by a workers militia as part of the socialist revolution.

This exhibition has been organised by the Parliamentary Archives with the support of the History of Parliament, Royal Holloway, University of London and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (TECHNE Creative Economy Engagement Fellowship).

Images in the exhibition have been used with the permission of:

Chetham’s Library, Manchester

Curator’s Office, Palace of Westminster

House of Lords Library

National Portrait Gallery, London

Parliamentary Archives

The Trustees of the British Museum

University of Manchester Library