NOVEMBER 1984 opened with a miners’ special delegate conference endorsing a plan to widen the dispute throughout the labour and trade union movement.

That demand was growing throughout the working class as union after union fell foul of the Tory anti-trade union legislation.

Nine unions at British Leyland car plants were issued with writs on November 5th and ordered to stop strike action over pay as they had not balloted under the legislation.

The courts were especially active on that day with the High Court ordering Cardiff dockers to lift their black on two scab haulage firms.

After 35 weeks of the strike, the TUC finally got round to setting up a hardship fund for the miners. This move was correctly interpreted by miners as being a sop following the refusal of the TUC to deliver any of the industrial action it had promised.

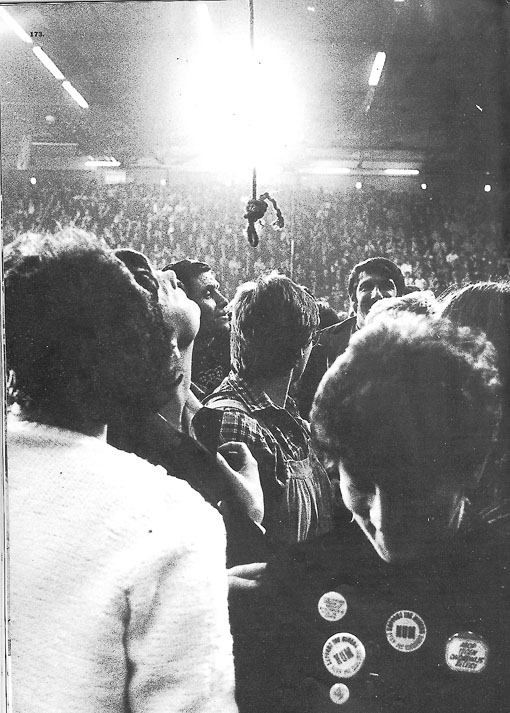

The anger and disgust of the miners towards the TUC bureaucracy reached new heights on November 13th when the newly elected general secretary of the TUC, Norman Willis, spoke at a rally of Welsh miners and their families in Aberavon.

Willis’s speech was absolutely offensive as he blamed pickets for the violence.

Amidst boos and jeers a symbolic noose was lowered by miners in the hall’s gallery above his head.

For his attack on the miners Willis naturally earned the praise of the Tory press, Tory MPs and Neil Kinnock the following day.

On November 23rd the funeral of two young victims of Thatcher’s attack on the mining communities took place.

Paul and Darren Holmes (aged 15 and 14) from the Yorkshire village of Goldthorpe were killed as they dug for coal to heat the family home on a railway embankment.

At a rally in Derby on November 24th, Scargill once again issued the call for other unions to take industrial action to halt the supply of coal and oil in line with TUC policy.

On the same day Thatcher made a speech in London which equated the NUM with terrorists.

By the end of the month, the High Court had removed miners’ leaders from control over NUM funds and appointed a receiver.

Back in September the Tories had publicly vowed that the miners’ strike would be over by Christmas, with every miner forced to crawl back through cold and starvation.

Thatcher had dramatically underestimated the determination and resistance of the miners and the refusal of the working class to see them starved into submission.

But this stubborn refusal was causing desperation in the ranks of the trade union bureaucracy and its Stalinist allies to break the strike.

This convergence between the TUC bureaucracy, Stalinism and the state was forced into the open in December 1984 by this determined struggle.

The Stalinists were forced into the open at a special delegate conference of the NUM called in London on December 3rd to discuss the threat to the union’s funds which had been sent abroad to avoid seizure by the court-appointed sequestrator.

At an executive meeting prior to the conference, Stalinists on the NUM executive joined with the right-wing in voting for a return of these funds to Britain where the courts could seize the £2,000 fine and by bowing to the Tory laws, purge the union’s contempt.

At the conference itself, delegates were shocked to see the Scottish delegation, led by the Stalinist chairman of the Communist Party, George Bolton, voting with delegates from areas which were scabbing in favour of appeasing the courts.

This position of appeasement was decisively rejected by the conference.

Delegates went on to call for a special General Council meeting of the TUC, demanding: ‘that the General Council mobilise industrial action to stop this most vicious threat in our history to the freedom and independence of British trade unionism’.

The issue was now clear: the demand that the TUC be forced to call a general strike, first advanced by the WRP and the ATUA, had now won the overwhelming support of the miners.

This was reinforced the following day when Scargill addressed a meeting in Goldthorpe, saying: ‘We are not asking for moral support or resolutions, we are asking now for practical assistance and we have asked the General Council to be convened to mobilise industrial action in support of this union.’

Labour leader Neil Kinnock quickly recognised the significance of this and he swiftly denounced all talk of a General Strike, claiming it would be ‘disastrous’ and ‘terminally damaging’.

Kinnock may have addressed his remarks to the working class but he was painfully aware that it was the capitalist class that faced disaster and terminal damage if a General Strike was called.

The General Council of the TUC were equally terrified and they flatly refused to call a special meeting of the Council. Instead they turned to the Tory government.

On December 10th they begged for a meeting and on the 14th they were granted one with the Energy Secretary, Peter Walker.

Scargill attacked this meeting, saying: ‘We don’t want the TUC or anyone else to go along and argue a case that effectively undermines the arguments of the NUM. We want the decisions of the TUC Conference in September put into practical effect.’

Hurling back in her face Thatcher’s boast that the miners would be starved back to work by Christmas, at every pit in the country a 24-hour picket was mounted over the Christmas period.

Having failed to crush the miners, the Tory government started the new year facing the economic cost of the strike.

Sterling plunged on the international money markets as the speculators woke up to the fact that the strength and determination of the miners and the working class had been severely underestimated.

A measure of the strength of solidarity within the working class can be gauged by the 100% backing given by railway workers for a one-day strike against victimisation.

This solidarity was in no small measure an expression of the outrage felt at the jailing of Kent miner, Terry French, for five years following a scuffle with a policeman on the picket line.

A young colleague of his, Chris Tazey, was jailed for three years.

Two days after his jailing, Terry French’s wife, Liz, spoke to a 2,000 strong audience at the Young Socialists’ Annual General Meeting, where she proudly stated that both her and Terry would continue the struggle for jobs.

This determination amongst miners and their wives expressed itself when on January 16th Derbyshire miners’ wives set off in thick snow on a four-day march.

The leadership of the TUC by now was keeping up a constant whine in public, matched by private scheming, that the strike had to be settled.

The TUC General Council met on 23rd January and faced a lobby of miners and members of the All Trades Union Alliance (ATUA) calling on the TUC to organise the General Strike.

But from this meeting there was no offer of further industrial support for the miners.

Strengthened by the TUC General Council refusal to act, Thatcher issued a decree on January 24th that the NUM must give a written undertaking to accept pit closures on other than economic grounds before talks could commence.

The Stalinist paper, Morning Star, jumped at this and suggested on January 25th that this condition was acceptable as, it claimed, the NUM had always accepted pit closure on other than economic grounds.

Scargill, backed by the NUM executive, refused Thatcher’s ultimatum, saying that he would never go ‘begging and crawling to the Coal Board for talks’.

On February 3rd, a conference of the ATUA in Sheffield, attended by over 2,000 delegates and visitors, recognised that the only way to ensure victory for the miners was through the mobilisation of the entire trade union and working class movement in a General Strike.

As we have said this was a demand that was winning growing support throughout the working class, which was facing attacks from the Tories on local services and jobs.

The TUC leaders were terrified that these struggles coming together with the miners’ action would inexorably lead to a General Strike and the inevitable struggle for power.

The Tory Government of Thatcher was itself in an extremely weak position, after nearly a year of throwing everything that the capitalist state had at the miners they had completely failed to break them.

A sign of this very real weakness is that the government’s dependence on the TUC bureaucracy grew rather than lessened towards the end of the strike.

Thatcher had famously refused to have any dealings with the unions and she completely ruled out any role for the TUC at the beginning of the strike.

Now, however, her position changed and the government sanctioned secret meetings between Norman Willis and MacGregor. Indeed, it was left to Willis to present the NCB’s ‘final offer’ to the NUM executive.

If the Tory government was relying on the TUC, the TUC itself was relying on the whole-hearted assistance of the Stalinists, who vehemently opposed the demand for a General Strike.

The position that began to emerge from the Stalinists centred around the demand for a ‘return to work with heads held high’.

This was first put forward as a ‘solution’ to the strike in the Morning Star and it would be raised on February 6th in South Wales, the area that finally moved the motion for a return to work nearly a month later with support from Communist Party members from the Maerdy Colliery.

On Thursday February 14, Willis informed the NUM executive that he had held secret talks with MacGregor and he presented them with a document that had been drawn up.

The executive rejected this document

On Monday, February 18th, the TUC leaders announced they were to visit Thatcher. Scargill made it clear that the NUM were not a party to these talks.

Thatcher would later record her ‘appreciation’ for the TUC.

Out of these talks the TUC submitted a second document to the NUM executive. This time Willis told them it was the best they could get.

An angry NUM executive declared that it was ‘100% worse’ than the first one and a delegate conference the following day unanimously rejected it.

After nearly one year out on strike, the mining communities and their supporters were far from weakened or defeated as demonstrated by a rally of 30,000 people in London on Sunday February 24th.

Scargill summed up his position on the role being played by the TUC when he addressed miners at Castleford on Tuesday 26th February, saying: ‘When history examines this dispute there will be a glaring omission – the fact that the trade union movement has been standing on the sidelines while this union has been battered.’

In fact, the TUC leaders had not merely sat upon the sidelines doing nothing. Their treacherous dealings with the government, their refusal to call industrial action as directed by the TUC Congress in support of the miners, the sanctioning of scabbing by some trade union leaders, in short their total betrayal of the miners, and through them the entire working class, had created the conditions where a return-to-work vote was narrowly passed by the delegate conference – moved as we have seen by the Stalinist-dominated South Wales area.

Yorkshire, Kent and Scotland voted against going back without the re-instatement of all the miners sacked during the dispute.

The motion to return to work on March 3rd was passed by the narrowest margin of 98 to 91, with Scargill remaining opposed to ending the strike.

The miners and their families endured enormous hardship in the course of this heroic struggle; 700 were sacked, a total of 11,312 people were arrested and fined and in some cases jailed for their stand against the destruction of the mining industry and defence of jobs.

In the case of David Gareth Jones and Joe Green they both gave their lives on the picket line to the struggle.

The one lesson that shines out from this magnificent fight and that should be burnt in the consciousness of every worker is that despite all the resources of the capitalist state being mobilised against the miners these alone were not sufficient to beat them.

The capitalist state for all its apparent strength had to rely on the treachery of the reformist trade union leaders and Stalinism.

The miners were not defeated in the strike they were betrayed by the TUC leadership.

With the return to work, every reformist and revisionist group, every middle class pessimist who lived in fear and awe of capitalism, proclaimed the strike to be at best a ‘heroic defeat’ that had inflicted a mortal blow from which the trade unions would never recover.

The Workers Revolutionary Party and its youth section, the Young Socialists, totally rejected this position, insisting that, far from being defeated, the miners had fought the capitalist state to a standstill.

The Young Socialists immediately set about proving in practice the undefeated nature of the working class by organising the March to Release the Jailed Miners and re-instatement of those who had been sacked.

The six-week long march set off on 18th May 1985 from Bilston Glen Colliery in Scotland, a fortnight later two more legs of the march set off from Swansea and Liverpool.

On 13th June, the NUM national executive committee issued the following statement:

‘The letter from the Young Socialists was read to the National Executive which, following discussion, agreed: 1) Any Area or member of the National Executive Committee who wishes to attend any part of the march should be entitled to do so. 2) The NUM reaffirms its total commitment to the campaign for the release of jailed miners and the reinstatement of those dismissed.’

Above all these marches won massive support from miners and the entire working class which ensured that they were fed and sheltered every day and night that they spent on the road.

The climax of the marches was a rally attended by over 4,000 at Alexandra Pavilion in north London on Sunday 30th June.

This rally showed the undefeated nature of the working class and the reliance of the state on the treacherous leadership of the trade unions.

Today these lessons could not be more vital as the working class confronts the immediate task of completing the fight waged by the miners in their year-long struggle by settling accounts once and for all with capitalism by kicking out these leaders and going forward to the socialist revolution.