In a landmark judgment on Friday in the High Court in London, the UK’s detention policy in Afghanistan was declared unlawful.

Since November 2009, the UK’s policy has involved internment for the purposes of interrogation for weeks or months beyond the permitted 96 hours under International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) guidelines.

The Judge, Justice Leggatt, found that detention or internment beyond the 96 hours ‘went beyond the legal powers available to the UK’ (para 423). Following the ruling, Phil Shiner of Public Interest Lawyers (PIL) said: ‘This is a judgment of profound importance with far reaching implications for future UK operations abroad where UK personnel are on the ground.

‘It tells the MoD again that no matter how they try to avoid accountability for the UK’s actions abroad, International Human Rights Law will apply and, thus, UK personnel must act accordingly. The solution is straightforward – the MoD must ensure that UK Armed Forces personnel, like civilian police, are trained to know what the law does and does not allow and that they must follow the rule of law or face the consequences.

‘This is yet another overseas human rights case which has been scrutinised very carefully by the courts and where the MoD has lost. The MoD, and not the Legal Aid fund, has to suffer the costs consequences where the state acts unlawfully and violates human rights overseas.’

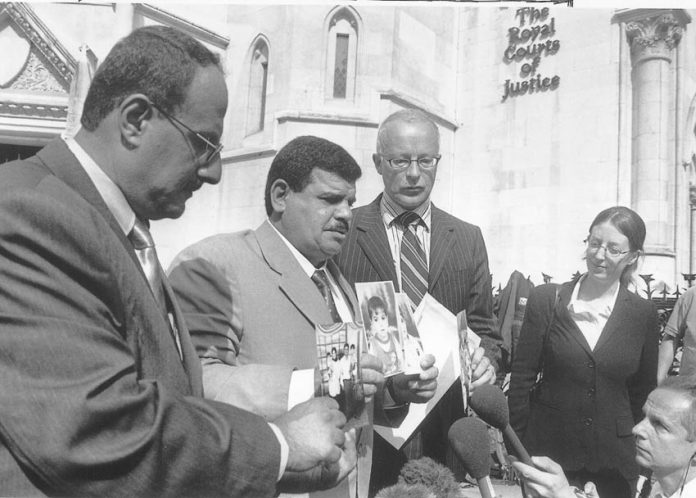

The case involved a Judicial Review of the Secretary of State’s policy. The Judicial Review was sought by three Afghan clients of PIL, joined with a claim for damages pursued by a client of Leigh Day & Co, Serdar Mohammed.

PIL’s participation at the hearing was by direction of the Court, in recognition of the significance of the judgment for the PIL claimants. PIL’s submissions were accepted by the Court on every point addressed.

The details of the PIL clients’ detention and internment are as follows:

• Mohammed Qasim was held at Camp Bastion, a UK military detention facility, from 19 September 2012 until the end of June 2013 (more than 9 months);

• Mohammed Nazim, a brother of the above, was arrested as part of the same UK mission on the same date and held for the same period at Camp Bastion;

• Abdullah (no surname) was held at Camp Bastion from August 2012 until the end of June 2013 (above 10 months).

The Judge had to decide a number of hugely important questions of law. The answers to all the following questions are almost completely reliant on various PIL cases pursued on behalf of Iraqi civilians in domestic courts or the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) over the last ten years or more.

Each case referred to below is a previous PIL case.

1. Did the Human Rights Act 1998 apply outside the territory of the UK and Northern Ireland and, thus, in Afghanistan?

The Judge held it did, relying on the case of Al-Skeini, House of Lords, June 2007.

2. Did the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) apply outside Europe and, thus, in Afghanistan?

The Judge held it did, relying on the case of Al-Skeini ECHR, Grand Chamber, July 2012.

3. Were the actions of the UK, as part of ISAF, attributable to the UK or the UN?

The Judge held they were attributable to the UK, relying on the case of Al-Jedda, ECHR, Grand Chamber, July 2011.

4. Were the rights of Article 5 ECHR (the right not to be arbitrarily detained and to due process) displaced by the operation of the various UN Security Council Resolutions forming the mandate in Afghanistan since October 2011?

The Judge held not, relying on the Grand Chamber decision of July 2011 in Al-Jedda referred to above.

5. Were the rights of Article 5 otherwise displaced or qualified by the operation of International Humanitarian Law (IHL)?

The Judge held not, relying on various decisions of the International Court of Justice or the ECHR. PIL says the implications of this judgment, following the Al-Jedda case to similar effect in the context of the relevant UNSCRs in Iraq, are of profound importance, and include the following:

1. That there is HRA 1998 applicability and ECHR jurisdiction in Afghanistan.

This finding from Afghanistan is likely to put further pressure on the MoD to ensure that its armed forces personnel are properly trained in what International Human Rights Law requires in extraterritorial conflict.

2. That merely because the UN had authorised ISAF to assist the Afghan government restore peace to the region did not mean the UK could escape liability for its actions in Afghanistan by claiming those actions were attributable to the UN.

This finding must mean that in future UN-mandated extra-territorial conflicts involving the UK, the SSD must proceed on the basis that UK actions will be attributable to the UK.

3. That International Human Rights Law cannot be displaced by the operation of a UNSC Resolution.

This finding must mean that in future UN-mandated extra-territorial conflicts involving the UK, the Secretary of State for Defence must proceed on the basis that International Human Rights Law will continue to apply.

4. That International Human Rights Law cannot be displaced by the operation of International Humanitarian Law and its ‘minimum standards’. This finding is of critical importance.

In Iraq, legal advice from Christopher Greenwood QC (as he then was) and James Eadie (counsel to the Secretary of State for Defence in this case) was that ‘the lex specialis of IHL operates to oust the ECHR’.

That approach is now definitively unlawful.

5. That these four claimants (and any other Afghans unlawfully detained pursuant to the same UK detention policy since November 2009) are entitled to substantial damages.

• Amnesty International has reviewed all 45 reported US drone strikes in Pakistan from January 2012 to August 2013, and conducted detailed research on nine separate drone strike cases in North Waziristan.

Amnesty says it went to great lengths to verify as much of the information obtained in its research as possible.

‘However, due to the challenges of obtaining accurate information on US drone strikes in North Waziristan, we cannot be certain about all the facts of these cases,’ the human rights group admitted. The full picture will only come to light when the US authorities, and to a lesser extent the Pakistani authorities, fully disclose the facts, circumstances and legal basis for each of these drone strikes.’

Nevertheless, one of Amnesty’s documented reports is enough to reveal the outright brutality and devastation of unmanned drone strikes.

Mamana Bibi, aged 68, was tending her crops in Ghundi Kala village on the afternoon of 24 October 2012, when she was killed instantly by two Hellfire missiles fired from a drone aircraft.

‘She was standing in our family fields gathering okra to cook that evening,’ recalled Zubair Rehman, one of Mamana Bibi’s grandsons, who was about 119ft away also working in the fields at the time.

Mamana Bibi’s three granddaughters: Nabeela (aged eight), Asma (aged seven) and Naeema (aged five) were also in the field, around 115 and 92ft away.

Around 92ft to the south, another of Mamana Bibi’s grandsons, 15-year-old Rehman Saeed, was walking home from school with his friend, Shahidullah, also aged 15.

Asma and Nabeela both sustained shrapnel injuries to their arms and shoulders. Shahidullah received shrapnel injuries to his lower back while Rehman Saeed sustained a minor shrapnel injury to his foot.

But three-year-old Safdar, who had been standing on the roof of their home, fell 10ft to the ground, fracturing several bones in his chest and shoulders. Because he did not receive immediate specialist medical care, he continues to suffer complications from the injury.

Zubair too required specialist medical care after a piece of shrapnel lodged in his leg. According to his father Rafeequl Rehman, Zubair underwent surgery several times in Agency Headquarters Hospital Miran Shah.

‘But the doctors didn’t succeed in removing the piece of shrapnel from his leg,’ he said. ”They were saying that his leg will be removed or he will die.’

Distraught at the loss of his mother and the prospect that his eldest son may be crippled by the attack, Rafeequl took Zubair to Ali Medical Centre in Islamabad but could not afford the medical fees.

‘So,’ he explained, ‘we decided to take him to Khattak Medical Centre in Peshawar and, after selling some land, we could afford the operation for him.’

Doctors at the hospital successfully removed the shrapnel and Zubair is now making a full physical recovery. A few minutes after the first strike, a second volley of drone missiles was fired, hitting a vacant area of the field around 9ft from where Mamana Bibi was killed.

Mamana Bibi’s grandsons Kaleemul and Samadur Rehman were there, having rushed to the scene when the first volley struck. As the two boys surveyed the area, they discovered their grandmother had been blown to pieces.

Fearing further attacks, the two tried to flee the area when the second volley of missiles was fired. aleemul was hit by shrapnel, breaking his left leg and suffering a large, deep gash to that thigh. The family home was badly damaged in the strikes, with two rooms rendered uninhabitable.

In total, nine people – all of them children except Kaleemul Rehman – were injured in the drone strikes that killed Mamana Bibi.

‘I’m still in shock over my grandmother’s killing,’ said Zubair. ‘We used to gather in her room at night and she’d tell us stories.

‘Sometimes we’d massage her feet because they were sore from working all day.’

Asma added: ‘I miss my grandmother, she used to give us pocket money and took us with her wherever she went.’