MONDAY was New Zealand’s Labour Day, an annual public holiday falling on the 4th Monday of October, commemorating the struggle for an eight-hour working day.

On Labour Day government offices and many businesses close, while street parades and protest marches take place, voicing the importance of the struggle for workers’ rights. During the 19th century, workers in New Zealand tried to claim the right for an eight-hour working day.

In 1840, carpenter Samuel Parnell fought for this right in Wellington, NZ, and won. Labour Day was first celebrated in New Zealand on October 28, 1890, when thousands of workers paraded in the main city centres, government employees were given the day off to attend the parades and many businesses closed for at least part of the day.

The first official Labour Day public holiday in New Zealand was celebrated on the second Wednesday in October in 1900. The holiday was moved to the fourth Monday of October in 1910 and has remained on this date since then. That struggle has roots going back to when the first ships arrived in New Zealand with people wanting to begin a new life in the colony.

By that time the industrial revolution was in full swing and the horrors of unregulated working days was being reflected in stunted growth and early death. Child labour was common and the working day was usually 10-16 hours a day for a six-day working week. Early socialist thinkers like Robert Owen in the UK had popularised the idea of 8-hours work, 8-hours rest and 8-hours play as a basic right in the early 1800s.

Karl Marx saw it as of vital importance to the workers’ health, saying in Capital: ‘By extending the working day, therefore, capitalist production… not only produces a deterioration of human labour power by robbing it of its normal moral and physical conditions of development and activity, but also produces the premature exhaustion and death of this labour power itself.’

One early emigrant on the Ship Duke of Roxburgh in 1839 was a carpenter and joiner by the name of Samuel Duncan Parnell. He had previously worked in a large London joinery establishment with co-workers he described as ‘a lot of the most red-hot radicals’. At the time in London, 12 or 14-hour days were standard.

The Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, Te Ara, explains what happened next on Parnell’s voyage to New Zealand: Among Parnell’s fellow passengers was a shipping agent, George Hunter, who, soon after their arrival, asked Parnell to erect a store for him. ‘I will do my best,’ replied Parnell, ‘but I must make this condition, Mr. Hunter, that on the job the hours shall only be eight for the day.’

Hunter demurred, this was preposterous; but Parnell insisted. ‘There are,’ he argued, ‘twenty-four hours per day given us; eight of these should be for work, eight for sleep, and the remaining eight for recreation and in which for men to do what little things they want for themselves. I am ready to start tomorrow morning at eight o’clock, but it must be on these terms or none at all.’

‘You know Mr Parnell,’ Hunter persisted, ‘that in London the bell rang at six o’clock, and if a man was not there ready to turn to he lost a quarter of a day.’ ‘We’re not in London,’ replied Parnell. He turned to go, but the agent called him back. There were very few tradesmen in the young settlement and Hunter was forced to agree to Parnell’s terms. ‘And so,’ Parnell wrote later, ‘the first strike for eight hours a-day the world has ever seen, was settled on the spot.’

Other employers tried to impose the traditional long hours, but Parnell met incoming ships, talked to the workmen and enlisted their support. A workers’ meeting in October 1840, held outside German Brown’s (later Barrett’s) Hotel on Lambton Quay, is said to have resolved, on the motion of William Taylor, seconded by Edwin Ticehurst, to work eight hours a day, from 8am-to-5 pm, ‘anyone offending to be ducked into the harbour’.

The eight hour working day thus became established in the Wellington settlement. ‘I arrived here in June, 1841,’ a settler told the Evening Post in 1885, ‘found employment on my landing, and also to my surprise was informed that eight hours was a day’s work, and it has been ever since.’

The last resistance was broken, according to Parnell, when labourers who were building the road along the harbour to the Hutt Valley in 1841 downed tools because they were ordered to work longer hours. They did not resume work until the eight-hour day was conceded. However, there were no unions or laws that could enforce the practice for most workers.

Whilst it remained a condition in most trades where labour shortages often prevailed and the building industry, it often wasn’t extended to other workers in the new colony. Within a few decades however unions began to be formed and agitation grew immediately for the establishment of a legal work day of eight hours. They became part of an international movement to limit the working day.

Women and children got a ten-hour day in England in 1847. French workers won a 12-hour day following a revolution in February 1848. The International Workingmen’s Association took up the demand for an eight-hour day at its convention in Geneva in August 1866, declaring: ‘The legal limitation of the working day is a preliminary condition without which all further attempts at improvements and emancipation of the working class must prove abortive, and The Congress proposes eight hours as the legal limit of the working day.’

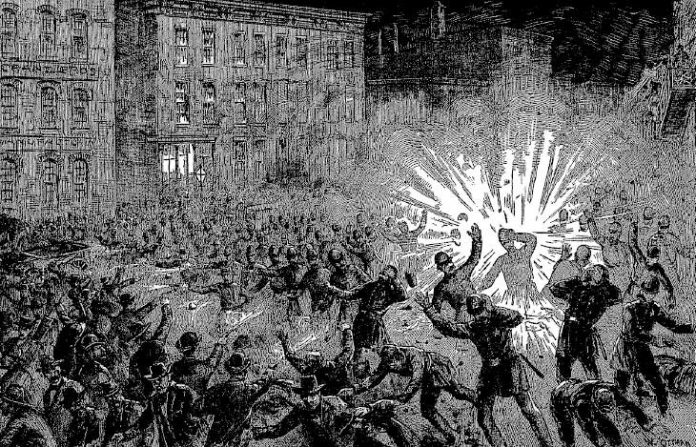

Te Ara picks up the story: Agitation for the eight-hour day spread throughout the industrialised world in the 1880s. On 3 May 1886 a workers’ eight-hour strike meeting in Chicago was fired on by police. The following day, at an indignation protest in Chicago’s Haymarket Square, a bomb was thrown, killing and wounding a number of policemen. Although the bomb thrower was never identified, eight anarchist labour activists were arrested, charged and convicted of conspiracy to murder. Four were executed, while one committed suicide in jail.

At an 1889 international labour congress in Paris, 1 May was adopted as a date to both demonstrate for an eight-hour working day and to commemorate the ‘Haymarket martyrs’. Since 1890 the celebration of May Day as the workers’ day has been adopted in a large number of countries. In New Zealand, however, Labour Day is held on the fourth Monday in October. New Zealand’s October Labour Day also has its origins in the 1880s eight-hour movement.

In 1890 New Zealand’s Maritime Council, consisting of the powerful transport and mining unions, called for a ‘labour demonstration day’. The day was to celebrate workers’ trades and to promote the eight-hour day. The date chosen, 28 October 1890, was the first anniversary of the Maritime Council’s foundation. The council itself did not survive the year, being destroyed in the collapse of the 1890 maritime strike.

Despite this set-back, the Labour Day demonstrations were a huge success in many parts of the country. Large processions were held in Dunedin, Christchurch and Wellington, with the 80-year-old Samuel Parnell leading the Wellington parade. In the 1890s Labour Day was not an official holiday, although government offices were closed on the day.

Richard Seddon’s Liberal government passed a law in 1899 declaring the second Wednesday in October as the Labour Day public holiday. In 1910 this was ‘Mondayised’, with the Labour Day holiday falling on the fourth Monday in October. While a Labour Day holiday had been gained, the union struggle to extend the eight-hour day to all workers continued… and continues today.