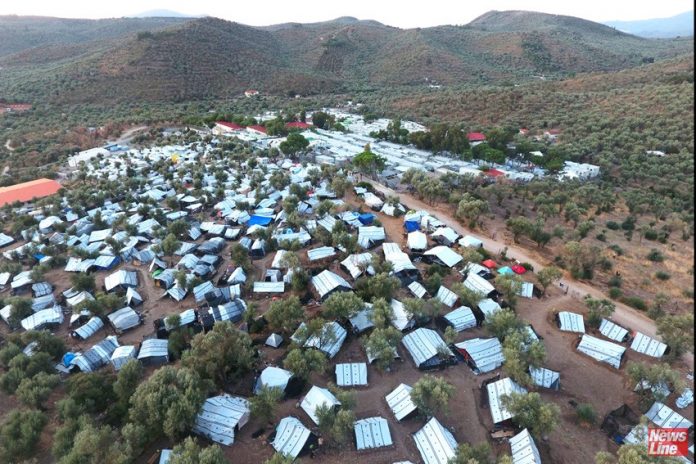

HUNDREDS of pregnant women, unaccompanied children and survivors of torture are being abandoned in refugee camps on the Greek islands, an Oxfam report revealed on Wednesday. At the end of December, the Moria camp in Lesvos was at around double its official capacity of 3,100 places, with just under 5,000 migrants living inside the camp and another 2,000 in an informal camp next to Moria, known as the Olive Grove.

Oxfam’s report details how the system to identify and protect the most vulnerable people has broken down due to chronic understaffing and flawed processes. For much of the last year there has been just one government-appointed doctor in Lesvos who was responsible for screening as many as 2,000 people arriving each month.

In November, there was no doctor at all so there were no medical screenings happening to identify the most vulnerable people. The existing procedures were already confusing because they have changed three times in the past year alone. The Oxfam report ‘Vulnerable and abandoned’ includes accounts of mothers being sent away from hospital to live in a tent as early as four days after giving birth by Caesarean section.

It tells of survivors of sexual violence and other traumas living in a camp where fights break out regularly and where two thirds of residents say they never feel safe. Hundreds of vulnerable people are being lumped together to live in the EU ‘hotspot’ camp of Moria which is at twice its capacity.

Renata Rendón, Oxfam’s Head of Mission in Greece, said: ‘It is irresponsible and reckless to fail to recognise the most vulnerable people and respond to their needs.

‘Our partners have met mothers with newborn babies sleeping in tents, and teenagers wrongly registered as adults being locked up. Surely identifying and providing for the needs of such people is the most basic duty of the Greek government and its European partners.’

Under Greek and EU law, the legal definition of vulnerability specifically includes unaccompanied children, women who are pregnant or with young babies, people with disabilities and survivors of torture, among others. The daily living conditions for migrants on the Greek islands compound the challenges for vulnerable people:

Moria camp is severely overcrowded at double its capacity, and has often been at more than three times its capacity in 2018.

Vulnerable people are theoretically allowed to leave the islands. However, the accommodation for people seeking asylum on the mainland is also insufficient, and according to the UNHCR, more than 4,000 people eligible for transfer were stuck on the islands of Lesvos and Samos in November.

Every year, conditions in and around the camp deteriorate further with the onset of winter because it is not equipped for cold temperatures, heavy rain and snowfall. While the Greek government is directly responsible for many of the procedural failures and the abysmal conditions in which people seeking asylum on the Greek islands live, European Union member states, too, are responsible for this crisis due to their refusal to share responsibility for hosting people seeking asylum.

People who arrive on the Greek islands have often suffered traumatic experiences.

Many have fled conflict and persecution in their home countries, experienced abuse, violence and exploitation at the hands of human traffickers, state officials and others on their journey, and survived a dangerous sea crossing from Turkey to Greece.

Most people come from countries ravaged by war and violence such as Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, and have been forced to leave their family, homes, jobs, or studies behind only to find themselves at risk of abuse, violence and exploitation during their journey.

They should have access to the normal Greek asylum process instead of a fast-tracked process designed to send them back to Turkey. They should be given suitable accommodation and appropriate medical care on the mainland.

Oxfam said there was a particularly worrying trend of authorities detaining teenagers and survivors of torture after failing to recognise them as vulnerable. Legal and social workers told Oxfam they frequently came across detainees who should not have been locked up because of their age or because of poor physical or mental health.

Once in detention, it is even more difficult for them to get the medical or psychological help they need. In one case, a 28-year-old asylum seeker from Cameroon was locked up for five months based on his nationality, despite having serious mental health issues.

No one checked his physical and mental health before he was detained, and it took a month for him to see a psychologist. He said: ‘We had just two hours a day when we were allowed to get out of the container … The rest of the time you are sitting in a small space with 15 other men who all have their own problems.’

Winter has brought heavy rain to Lesvos turning the tented areas of the camp into a muddy bog. The temperature is expected to drop below freezing in the next week and there could be snow. Desperate to keep warm, people burn anything they can find including plastic and they take dangerous improvised heaters into their tents.

The situation is particularly unbearable for the people who live in the Olive Grove. The tents, which are often simply bought from local stores, are pitched on a sandy hill, and muddy streams of water run through the camp whenever it rains, frequently flooding the floors of tents and the few belongings people have.

Rendón added: ‘Local authorities and humanitarian groups are making efforts to improve conditions in places like Lesvos. Unfortunately, this is made almost impossible by policies supported by the Greek government and EU that keep people trapped on the islands for indefinite periods.’

The report is illustrated with comments from those with experience of the camp at Moria. ‘The situation in Moria is beyond the limits of the imagination. I have been visiting the camp since 2017. Every time you think it cannot get any worse, it does,’

said Maria, a social worker for Oxfam’s partner, the Greek Council for Refugees (GCR).

‘I see Moria as hell. I know women who gave birth, they had a C-section delivery and after four days they were returned to Moria with their newborn babies. They have to recover under dirty, unhealthy conditions,’ said Sonia Andreu, manager at the ‘Bashira Centre’ for migrant women in Lesvos.

‘70 people have to share one toilet, so hygiene is very bad. There are many small children and babies in the camp. Sometimes people do not even have a tent and winter is coming. In the Olive Grove, there are snakes, scorpions and rats,’ said ‘John’, who works with an NGO in Lesvos (name changed).

‘We sleep with 25 women in one tent and we all share one toilet. That’s a problem in itself, and because of the lack of regulation anyone can use our toilet. ‘The toilets are really dirty, and women wash themselves there, too. This means they get vaginal diseases and there is no medicine available,’ said ‘Clara’, 36, from Cameroon who lives in Moria camp (name changed).

Oxfam is calling for the Greek government and EU member states to deploy more expert staff, including doctors and psychologists, and to fix the screening system on the Greek islands. It said that more people seeking asylum should be transferred to mainland Greece on a regular basis – particularly the vulnerable.

Oxfam is also calling on EU member states to share responsibility for receiving asylum seekers with Greece more fairly by reforming the ‘Dublin Regulation’ in line with the position of the European Parliament.