THE ZIMBABWEAN government has arrested thirteen nurses who were protesting their deteriorating pay and working conditions. They have since been released on bail – but have been dismissed.

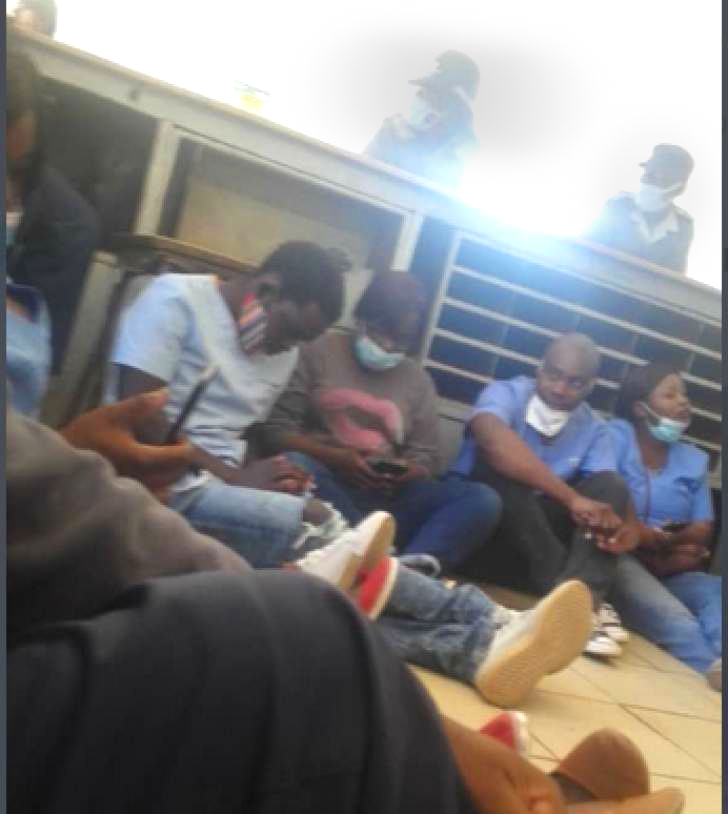

The arrests took place at the Harare hospital on 6 July, as nurses protested saying they could no longer survive on their monthly salary. They were released on bail but have been removed from the payroll and are facing charges for breaching Covid-19 regulations.

PSI (Public Services International) is demanding that all nurses be immediately reinstated, and that the Zimbabwe government cease intimidating and harassing health workers and instead listen to their legitimate demands and concerns.

According to PSI affiliate, the Zimbabwe Nurses Association (ZINA), this attack was initiated to prevent the nurses from organising a peaceful demonstration and is a gross violation of trade union and human rights.

ZINA had been on strike, with workers gathered in Harare and Bulawayo, to push for an upward salary review and outstanding Covid-19 allowances, as well as adequate provision of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE).

This was after the government had rendered the Bipartite Negotiating Panel for the sector useless when it unilaterally declared that it would not be engaging in any form of collective bargaining for the next three months.

Such contempt for ZINA’s trade union and labour rights to organise and collective bargaining is unacceptable.

With the inflation rate hovering around 1000%, the cost of living has risen so rapidly and steeply as to render public sector salaries almost worthless. In parallel, the government of Zimbabwe has spent millions of dollars on luxury cars for senior officials.

No wonder the workers are declaring that they have nothing more to lose. Some studies have calculated the cost of the food basket to be at $8,000.00 (approx 22USD) against a salary said to be around $3,000.00 (approx 8USD).

The negotiations should therefore not only address the short-term concerns of the workers, but should also put in mechanisms to sustainably cushion the workers against the run-away inflation.

We call on the Zimbabwe Government to reverse its dictatorial stance, to ensure nurses and all other health workers are provided with adequate PPE, pay the outstanding Covid-19 allowances and return to the Bipartite Negotiating Panel for collective bargaining on ZINA’s legitimate demand for an upward review of the salaries of its members.

- South Africa is bracing for the worst of the coronavirus pandemic, with infections mounting at a rapid pace, doctors and nurses being worked to the bone and intensive-care units at risk of running out of beds.

The government imposed a strict lockdown in late March, just weeks after the first case was detected, which helped slow local transmission.

But the shuttering of most businesses proved unsustainable in a country already contending with a recession and rampant unemployment, and curbs were eased last month to enable millions of people to return to work.

The rate of new infections has surged since, especially in relatively poor urban areas, increasing by more than 8,000 for each of the past nine days to reach 238,339 on Thursday.

‘The storm that we have consistently warned South Africans about is now arriving,’ health minister Zweli Mkhize told lawmakers on Wednesday.

In fact while South Africa has the most confirmed cases in Africa, it’s also tested more than 2 million people and screened about a third of the population of 60 million.

Fewer people were infected in May and June than was previously predicted under optimistic scenarios, Mkhize said, and the peak of the outbreak, expected by mid-August, may be at a lower level than initially feared.

Despite the government’s preparations, ‘bed capacity is still expected to be breached or overwhelmed in all provinces,’ Mkhize said.

Some public hospitals are already struggling with an increased patient load and the loss of staff who’ve contracted Covid-19. Nationwide, 377 doctors and 2,473 nurses have been infected, latest data from the Health Ministry shows.

Health workers are ‘burnt out, they are stressed, they see their colleagues getting sick and are worried that there are not enough personnel helping them,’ said Angelique Coetzee, a doctor who chairs the South African Medical Association.

Numerous panels have been set up to deal with the crisis, but more attention should be given to providing care to those who fall ill, she said.

While the disease was initially concentrated in Cape Town, it has since taken off in Johannesburg, the economic hub and biggest city, and in Pretoria, the capital.

Infections have also spiked in towns in the Eastern Cape province, which have inferior resources to the main cities.

‘There are signs that the health care system is collapsing both in the public and private sector,’ said Zwelake Tywala, a National Health and Allied Workers Union official in the Eastern Cape.

‘There isn’t any management or leadership from the side of the hospitals. We’re very worried.’

The government is taking steps to address the shortcomings in state hospitals, including contracting in more beds from private hospitals, recalling nurses from study leave and rehiring some who had retired, said Sandile Buthelezi, the director-general of the Department of Health.

It’s also trying to entice health practitioners who have been working abroad to return, and to hire more from Cuba and other countries, he said.

Some officials suggest that stringent lockdown rules should be reimposed. President Cyril Ramaphosa has ruled out that option, saying people need to earn a living and take responsibility for their own health by wearing masks, washing their hands and exercising social distancing as much as possible.

That’s not happening in many areas, with people congregating at church services and funerals. Commuters who rely on public transport aren’t able to maintain physical distancing as many drivers defy rules to restrict passenger loads to 70% of normal capacity.

A number of hospitals were already struggling to meet patients’ needs and were badly run before the virus struck, and have now reached a tipping point, Coetzee said.

‘Covid is exposing all these problems that were already in the healthcare system,’ she said. ‘It’s not a new thing.’