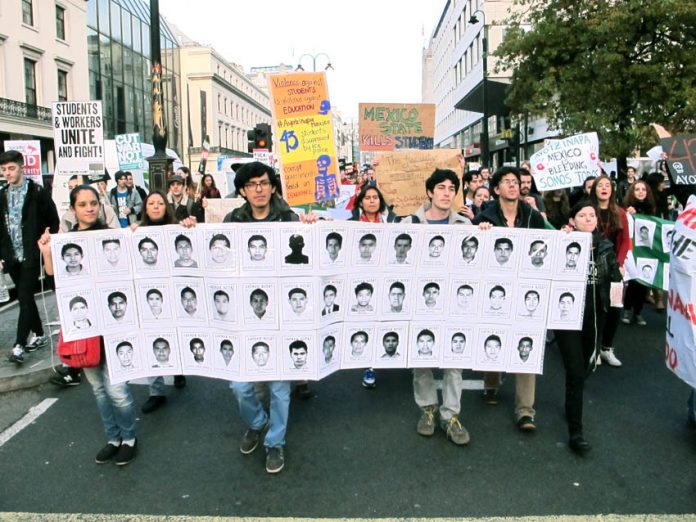

THE Attorney General of Mexico has failed to properly investigate all lines of inquiry into allegations of complicity by armed forces and others in authority in the enforced disappearance of the 43 students from the Ayotzinapa teacher college, said Amnesty International after meeting with family members of the victims.

At an Amnesty International press conference last weekend in Mexico City, experts gave a critique of the faltering investigations overseen by the Mexican Attorney General Jesus Murillo Karam and outlined the demands of the parents of the 43 students.

The Attorney General’s office said that all lines of enquiry have now been exhausted.

‘We have a catalogue of concerns over the way the investigation has been run and whether the full range of these crimes, including enforced disappearance and the killing of six people when the students were first attacked have been fully addressed,’ said Erika Guevara Rosas, Amnesty International’s Americas Director.

‘Amidst worries about the possible complicity of local government authorities and the army, it is all the more important that every line of investigation is thoroughly explored and that no stone is left unturned,’ Rosas added.

This latest call came the day after Austrian forensic scientists announced that they had been unable to identify the DNA from badly burned remains found in a mass grave.

Further tests on the samples could take months. The enforced disappearance of the students has highlighted Mexico’s appalling human rights record, said Amnesty.

More than 100,000 people have been killed in Mexico since the ‘war on drugs’ began in 2006 at least 23,000 are missing, according to official data.

Thousands of communities have been displaced by the increasing violence and Amnesty International continues to receive reports of human rights violations committed by police and security forces including arbitrary detentions, torture and enforced disappearances.

‘The disappearance of these students is a crime that has shocked the world. This tragedy has changed the distorted perception that the human rights situation has been improving in Mexico since President Peña Nieto took power.

‘There are thousands more cases that have barely been investigated in Mexico, they cannot be ignored anymore,’ said Erika Guevara Rosas.

She concluded: ‘Much more needs to be done to investigate the many cases where there are signs of collusion on the part of the authorities and security forces in human rights abuses, for example the mass execution of civilians in Tlatlaya and the massacres of migrants.

‘Tragically, impunity for these terrible crimes remains the norm. Federal and state institutions are failing to fulfil their human rights obligations, sending the message that these abuses are actually allowed.’

Meanwhile, on Monday the decapitated body of a journalist who was abducted by armed men three weeks ago has been discovered in Veracruz state in the east of Mexico.

Officials claimed that a former police officer had admitted carrying the killing of the reporter at the request of the town’s mayor.

Officials said the mutilated body of Moises Sanchez was discovered last Saturday on the outskirts of the town of Medellin de Bravo.

Sanchez was a social activist who also published a weekly newspaper, La Union, which covered local government corruption and violent deaths, as well as publishing citizen’s complaints.

The disappearance on January 2 of the reporter had sparked protests in Veracruz state, where at least 11 journalists have been killed since December 2010.

The state is one of the most perilous places in Mexico for reporters to work.

Carlos Lauría, of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), said at the time of his disappearance: ‘Veracruz authorities have a history of denigrating the activities of local journalists and a miserable record of impunity in cases of crimes against journalists.’

A CPJ statement on Jnauary 5th said: ‘The Committee to Protect Journalists condemns the abduction of Mexican journalist José Moisés Sánchez Cerezo and calls on authorities to do their utmost to find him and apprehend the perpetrators.

‘Several unidentified armed men kidnapped Sánchez from his home in the municipality of Medellín de Bravo in central Veracruz on Friday evening and seized the journalist’s computer, camera and other electronic materials, according to news reports.

‘The journalist has not been seen or heard from since,’ the reports said. Sánchez worked as a taxi driver and used the money he earned to fund La Unión, a small weekly print and online newspaper that covered local events in Medellín de Bravo.

‘The paper often criticized city authorities, particularly the mayor, Omar Cruz Reyes, and denounced local criminal activity as well as the poor quality of basic services like garbage pickup and the absence of street lights.

‘A local journalist who asked to remain anonymous for fear of reprisal told CPJ that Sánchez had not published a print edition in months due to financial constraints. The last story published on La Unión’s website dates to April, according to CPJ research.

‘In recent months, according to local journalists and news reports, Sánchez had posted on Facebook critical commentary, links to articles, and videos. He also acted as a source for other Veracruz journalists, whom he often provided with photographs and other information.

‘In the days before his kidnapping, the journalist posted on Facebook several photographs of protests against the governor, Javier Duarte de Ochoa, as well as links to articles about a recent murder.

‘On December 13 and 14, he posted several articles, press releases, and a video regarding the formation of a neighbourhood watch self-defence group in response to local crime.

‘It wasn’t clear whether Sánchez was the author of any of the material posted on Facebook. Besides reporting on its activities, Sánchez was active in the group, according to local news reports.

‘The journalist who asked to remain anonymous told CPJ that information about self-defence groups was particularly sensitive for local officials who sought to downplay shortcomings in local law enforcement.

‘The journalist’s son, Jorge Sánchez, said that his father had been threatened by the mayor in connection with his coverage of the groups.

‘In a press conference on Monday, the mayor denied any link to the kidnapping and said he would cooperate with the investigation. State authorities said in a press release today that several municipal police officers had been detained for questioning in connection with the crime, but did not offer further details.

‘In a press conference on Saturday, Governor Duarte referred to Sánchez as an “activist and taxi driver”. On Sunday, after criticism from local reporters, the state spokesman posted on social media that the governor had met with Sanchez’s family and referred to him as a journalist, according to news reports.

‘Veracruz authorities have a history of denigrating the activities of local journalists and a miserable record of impunity in cases of crimes against journalists,’ said Carlos Lauría, CPJ”s senior programme3 coordinator for the Americas. ‘Local authorities must immediately find José Moisés Sánchez Cerezo and bring him home safely and ensure his kidnappers are brought to justice.’

Veracruz is one of the most dangerous states in Mexico for the press, according to CPJ research. Since 2011, at least three journalists have been killed in Veracruz in relation to their work, according to CPJ research.

CPJ is investigating the deaths of at least six others in unclear circumstances. At least three journalists have disappeared in the state in the same time period. In the past, Governor Duarte’s government has sought to dismiss any possible link between journalists’ murders and their profession.

Violence tied to drug trafficking has made Mexico one of the most dangerous countries in the world for the press, according to CPJ research. More than 50 journalists have been killed or have disappeared since 2007. The country was ranked seventh on CPJ’s 2014 Impunity Index, which spotlights countries where journalists are slain and the killers go free.