TODAY is the 200th anniversary of the birth, on 28th November, 1820, of Frederick Engels, the closest collaborator, benefactor, friend and comrade of Karl Marx.

Engels was born in November 1820 in the Rhineland town of Barmen.

This town was known with good reason as the ‘German Manchester’, a heavily industrialised, polluted town dominated by the cloth industry and by austere Calvinist Protestantism.

The Engels family were wealthy factory owners with interests in cotton and bleaching and from his earliest days he was familiar with and grew up amongst the effects of industrialisation, the stinking pollution of the dye works, the poverty of the workers and the immense wealth of the industrialists who exploited them.

The career path for the young Engels was firmly established by the family. At the age of 17, he was removed from education and sent to the city of Bremen to be inducted into the family business by learning about the industry as a clerk to a firm of linen exporters.

To assuage the deadly boredom, Engels wrote articles in newspapers that were critiques of the conditions of workers and the social costs of industrialisation. He had naturally not yet formulated any critique of capitalism per se.

His ire was directed at the stultifying effects of Calvinism and the social costs of the Protestant work ethic with the misery it imposed on factory workers.

In 1841, bored with being deskbound in Bremen, Engels returned home to a life that he found equally tedious.

To escape he, later that year, volunteered for one year’s service with the Royal Prussian Guards Artillery, based in the capital Berlin.

In Berlin, he came into contact with the Young Hegelian movement.

Engels said of the Young Hegelians that some, including himself, ‘contended for the insufficiency of political change and declared their opinion to be that a social revolution based upon common property, was the only state of mankind agreeing with their abstract principles.’

Both Engels and Marx associated with the ‘Young Hegelians’, inspired by the revolutionary essence of the great German idealist philosopher George Hegel, and attracted by his dialectical method which espoused constant development and change through contradiction.

After his military service in 1842, the family sent Engels to Manchester to work in the family firm, a multi-national cotton-thread business.

Manchester in the 1840s was a crucible of the industrial revolution and Engels found himself working and living in a community dominated by the cotton manufacturers.

Here he came face to face with unbridled capitalist exploitation and the degradation of the working class.

He wrote later: ‘A few days in my old man’s factory have sufficed to bring me face to face with its beastliness, which I had rather overlooked.’

Although forced to work alongside the bourgeoisie, he made a point of not socialising with them. He wrote: ‘I forsook the company and the dinner parties, the port wine and champagne of the middle classes, and devoted my leisure hours almost exclusively to the intercourse with plain working men.’

Aged just 24, Engels, guided by Mary Burns a radical young working class Irishwoman who became his lifelong companion, witnessed capitalist industrialisation more extensive, repressive and exploitative than any he had seen in Germany.

In his first major book, ‘The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844’, Engels reports in excruciating detail the miseries of child labour, starvation wages and appalling working conditions, resulting in crippling injuries or deformities even among the youngest workers.

He called living conditions in English industrial towns ‘the highest and most unconcealed pinnacle of social misery existing in our day’.

Accompanied by Mary, he witnessed and heard from their own mouths the conditions endured by workers and their families.

Engels wrote: ‘It is utterly indifferent to the English bourgeois whether his working-men starve or not, if only he makes money. All the conditions of life are measured by money, and what brings no money is nonsense, unpractical, idealistic bosh.’

Engels observed the rapid rise of illegal trade unionism.

He wrote: ‘The incredible frequency of these strikes proves best of all to what extent the social war has broken out all over England.

‘No week passes, scarcely a day, indeed, when there is not a strike in some direction.’

Many liberals had bemoaned the wretched inhuman conditions of the working class but they saw it as a helpless class that deserved the ‘help’ of their liberal superiors.

But ‘Condition of the Working Class in England’ was much more than just an exposé of the inhumanity of capitalism.

Engels was the first to understand that this oppressed mass was not just an exploited working class but the only class that could liberate mankind from capitalism – capitalism for Engels had created in the working class its own ‘gravedigger’.

The book created an immediate sensation in German radical circles (it was at first only published in Germany).

Karl Marx was particularly enthusiastic about it.

Engels returned to Germany in 1845 and on his way back, he stopped in Paris, where he met Karl Marx.

A lifelong intellectual rapport was then established between them and, finding they were of the same opinion about nearly everything, they decided to collaborate on their writing.

This meeting in Paris was to cement the lifelong friendship and comradeship between the two men.

Marx had been forced out of Prussia earlier and had arrived in Paris in October 1843 where he quickly immersed himself in study and in meeting with French workers.

Like Engels, Marx regarded the working class, the propertyless class, as having the historic mission of liberating mankind from the yoke of capitalism.

Engels himself wrote: ‘When I visited Marx in Paris in the summer of 1844, our complete agreement in all theoretical fields became evident and our joint work dates from that time.’

As young men in Germany, Marx and Engels followed the same philosophical path even before they met.

They had both been involved as ‘Young Hegelians’, inspired by the revolutionary essence of Hegel’s dialectic and its espousal of development through contradiction, in spite of Hegel’s belief that objective reality was an expression of the ‘Absolute Idea’.

The great limitation of Hegel was his idealism. For Hegel, changes occurred within the realms of ideas and changes in the material world were mere reflections of these changes.

Both Engels and Marx had been profoundly affected by the writing of Ludwig Feuerbach, the German philosopher who started as a follower of Hegel but who was to break with him and asserted the absolute primacy of the material world and, as Engels wrote, ‘placed materialism back on the throne’.

But both quickly understood that Feuerbach suffered the same limitation of the early materialists in that he saw man as a product of the material world whose thoughts and ideas were a reflection of nature, but Feuerbach still saw an individual man as just passively reflecting nature.

In rejecting Hegel’s idealism, Feuerbach had thrown out the active side of Hegelianism – namely that man does not merely passively reflect nature but is essentially in conflict with it.

As Marx put it in his eleventh thesis he wrote on Feuerbach: ‘Philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point however is to change it.’

Engels and Marx put this into practice throughout their lives in the struggle to build revolutionary movements.

From 1845 to 1847, Engels lived in Brussels and Paris combining theoretical writing and studies with practical activity amongst German workers there.

Along with Marx, he established contact with the secret German Communist League.

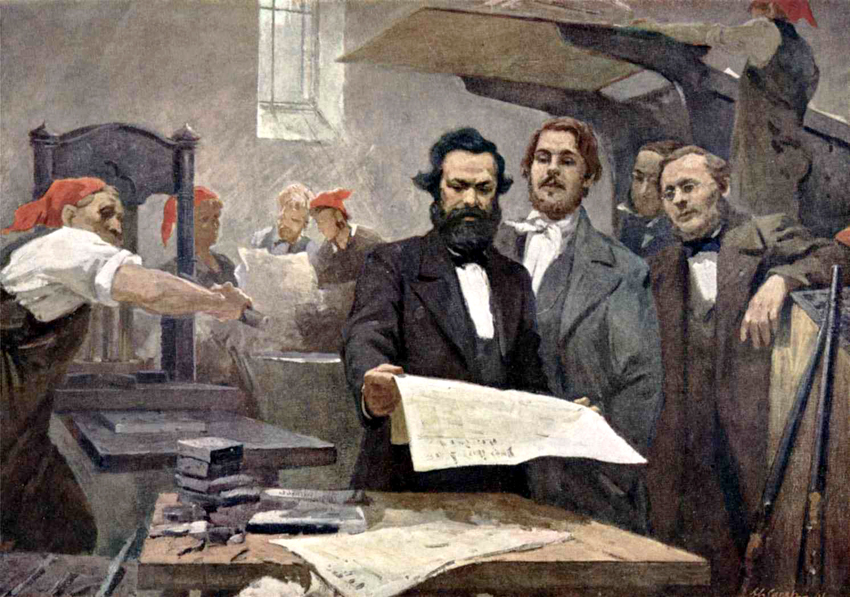

The Communist League commissioned Marx and Engels to write a manifesto setting out the main principles of socialism that they had worked on.

This was to be published as the famous Manifesto of the Communist Party in 1848.

It opens with the words: ‘A spectre is haunting Europe – the spectre of Communism’ and then it declares proudly: ‘Of all the classes that stand face to face with the bourgeoisie today, the proletariat alone is a really revolutionary class. The other classes decay and finally disappear in the face of modern industry; the proletariat is its special and essential product.’

It goes on: ‘What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own gravediggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable.’

The Manifesto concludes: ‘Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communist revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Working men of all countries, unite!’

The same year that the Manifesto was published, revolution broke out in France and spread rapidly throughout Western Europe.

Engels and Marx returned to Prussia and threw themselves into the democratic revolution against the Prussian autocracy.

The revolution was crushed and Marx was deported, ending up in London.

Engels remained and participated in the armed popular uprising until the rebels were defeated and he was forced to flee, returning to England in 1849.

In November 1850, unable to make a living as a writer in London and anxious to help support the penniless Marx, Engels returned to his father’s business in Manchester.

All the time, the two men kept an almost daily correspondence, exchanging ideas and opinions and collaborating in developing the theory of scientific socialism.

At the same time, they took a leading role in the struggle of workers in Britain and across the world.

In 1864, Marx and Engels founded the International Working Men’s Association which, in accordance with their idea of uniting workers of all countries, was to have a tremendous significance in the development of the international working class movement.

On July 1, 1869, Engels sold his share of the business to his partner and was finally able to put the ‘accursed’ job behind him and move to London to be close to Marx and increase their collaboration.

Some, including Engels himself, have painted his main contribution to the development of socialist theory as being that of Marx’s financial supporter who made it possible for Marx to carry out his monumental work on Capital.

This is far from the whole story.

Engels wrote numerous classic works of Marxism, including ‘Anti-Duhring’, ‘Dialectics of Nature’, ‘Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy’, ‘The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State’, and ‘Socialism: Utopian and Scientific’.

One of his most important works was a polemical work ‘Anti-Duhring’, published in 1876.

From this larger book the shorter work ‘Socialism: Utopian and Scientific’ was published in 1880 and it remains the best introduction to Marxist theory ever written – and certainly a book that every worker and young person would find invaluable in understanding the fundamentals of Marxism.

His classic work ‘The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State’, written in 1884, analyses the origins and essence of the state and Lenin described it as ‘one of the fundamental works of modern socialism’.

It provided the basis for Lenin’s book ‘State and Revolution’ (written in August- September 1917, just before the victory of the Bolshevik revolution in October) which analyses the role of the state in society and the necessity for proletarian revolution to overthrow the capitalist state.

Marx died in 1883 and Engels devoted his remaining years to editing Marx’s unfinished volumes of Capital, publishing the final twovolumes before his owndeath.

After Marx’s death, Engels insisted in relation to his role in the development of Marxism: ‘I cannot deny that both before and during my 40 years’ collaboration with Marx I had a certain independent share in laying the foundation of the theory, and more particularly in its elaboration. But the greater part of its leading basic principles, especially in the realm of economics and history, and, above all, their final trenchant formulation, belong to Marx.

‘What I contributed – at any rate with the exception of my work in a few special fields – Marx could very well have done without me.’

Engels died on 5th August 1895 in London, aged 74.

Lenin wrote on news of his death the following:

‘After his friend Karl Marx (who died in 1883), Engels was the finest scholar and teacher of the modern proletariat in the whole civilised world. From the time that fate brought Karl Marx and Frederick Engels together, the two friends devoted their life’s work to a common cause.’

Marx and Engels were the first to explain that socialism is not some good idea, an ‘invention of dreamers’, but ‘the final aim and necessary result of the development of the productive forces in modern society’.

Today with the world economic and political crisis of capitalism exploding everywhere, leading to revolutionary uprisings and struggles for workers’ power, the struggle to build the Marxist leadership to carry them forward to victory through the smashing of the capitalist state and advancing to the Dictatorship of the Proletariat is the burning issue.

Engels fought all his political life along with Marx to build precisely such revolutionary parties of the working class that would audaciously lead the struggle for power.

The way to celebrate Engels’ life today is to take forward his lifelong fight by building the International Committee of the Fourth International in every country to lead the world socialist revolution to victory.

• ‘Socialism Utopian and Scientific’ and other works by Engels, Marx, Lenin & Trotsky can be ordered online at

revolutionarybooks.co.uk