Turning the Tide – The 1966 seamen’s strike and the making of modern maritime trade unionism. An RMT pamphlet, available free from RMT head office, 39 Chalton Street, NW1 15D, London (Tel: 0207 387 4771)

PUBLISHED to mark the 50th anniversary of the then longest official strike since the first World War, Turning the Tide pays tribute to the heroism and determination of merchant seamen not to be treated as semi-slaves.

Under the 1895 Merchant Shipping Act, seafarers could be disciplined, have their pay docked, or be blacklisted for any number of petty offences. Also their union, the National Union of Seamen, had been run like a petty dictatorship by its founder Havelock Wilson.

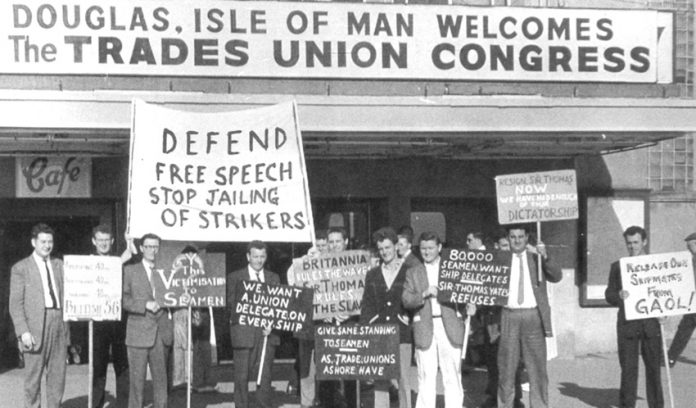

Unofficial strikes in 1947, 1948, 1955, 1960, 1962 and 1965 by frustrated members saw seamen jailed or expelled from the union. The 1966 strike was fought on the demand for a 40-hour week and £60 a month for an able seaman.

Outlining the union’s history the RMT pamphlet says that after a six-week national seamen’s strike in 1911 which won recognition from the shipowners and forced them to drop an anti-union pledge, Havelock Wilson changed from strike leader to ‘a man who saw his role as prioritising the shipowners’ commercial interests. Any opposition was vilified and silenced.’

And in 1926 ‘the NUS fell out with the rest of the trade union movement when, alone among unions, it refused to back the General Strike.’ Moving on to the 1966 strike, the pamphlet notes: ‘The 1966 strike was in many ways an explosion of pent-up grievances that seafarers had with shipowners, with the strict laws they had to work under – and to some extent with their own union …

‘The spark that lit the fuse was a walk-out by 200 crew members of the passenger liner Corinthia in Liverpool in July 1960 following the dismissal of a steward. ‘As in 1947, the strike leaders were jailed. This only stoked more fury against the way that legislation allowed seafarers to be imprisoned for “desertion” or “disobeying a lawful command” if they went on strike.

‘This time, however the strikers organised themselves. They set up an internal pressure group in the NUS, the National Seaman’s Reform Movement. Many of its leading activists would later play a prominent role in the 1966 strike.’

The strike took on the Harold Wilson Labour government as well as the shipowners and trade union bureaucracy. Under the heading: ‘Forty-seven days that shook the country’ the pamphlet takes readers through its twists and turns. This begins: ‘16 May – The NUS strike begins despite warnings from the Labour government that the union’s demands would breach its prices and incomes policy … Prime Minister Harold Wilson appears on television to warn that the strike decision “can only have grave consequences for our country”.

‘19 May – Within a few days there are 410 ships idle and 11,885 NUS members are on strike. Crews are walking off as soon as they reach a British port, and the union says the strike is solid. The pound has come under severe pressure and is being propped up by the sale of dollars from the Exchequer’s reserves.

‘23 May – The government declares a State of Emergency, giving it powers to clear ports and cargoes and to use troops to do dock work. Not since the 1955 railwaymen’s strike has a state of emergency been called in an industrial dispute.

‘25 May – The government sets up a Court of Inquiry under Lord Pearson … asked to come forward with proposals to end the dispute as quickly as possible …

‘31 May – … £38 million have been wiped off Britain’s gold and foreign currency reserves – double the amount in April …

‘7 June – …the TUC is asked to order a boycott of foreign vessels trading on the British coast …

‘8 June – The NUS executive council rejects the Pearson Inquiry’s proposal to phase-in a 40-hour week over two years …

‘9 June – The TUC rebuffs NUS approaches for other unions to give official support for the strike. Its leaders instead want the union to accept the Pearson proposals. However, rank and file trade unionists are giving industrial and financial help to the strikers.

‘13 June – Three thousand dockers in Hull stop work over cargo being boycotted by the strike. Dockers in London and Liverpool are also refusing to handle any “blacked” cargo …

‘20 June – In the House of Commons Harold Wilson denounces the union’s rejection of the Pearson recommendations … He goes on to accuse a “tightly knit group of politically motivated men” of exercising too much influence on the NUS executive council …

‘22 June – In a blow to the NUS, the TUC … formally decides not to extend the strike to sympathy action against non-British vessels in home ports …

‘23 June … Union general secretary Bill Hogarth warns, however, that public sympathy might be wavering following the prime minister’s dramatic “politically motivated men” allegation.

‘25 June – The shipowners table new, more generous proposals and by 26 votes to 17 the NUS executive council agrees to return to the the National Maritime Board for negotiations. These resume three days later – on the same day that there is another incendiary intervention by the prime minister.’

This came on 28 June when Wilson pursued his ‘red scare’ attack by naming ten ‘politically motivated men’ including Communist Party organisers Bert Ramelson and Dennis Goodwin, NUS EC members Jim Slater and Joe Kenny (whom Wilson conceded were not CP members but who he claimed have been ‘in continual contact’ with the others) and London dockers’ leaders Jack Dash and Danny Lyons. The RMT pamphlet notes that the Wilson speech showed ‘the police and security services have been prying into the lawful activities of trade unionists’.

The next day 29 June: ‘The NUS executive agrees by 29 votes to 16 to accept a new offer from the shipowners.’ Despite ‘a vocal group of members saying the union should have held out for its demands in full’ the strike ended at midnight on 30 June.

The RMT in its pamphlet salutes the heroic seafarers, and warns of the dangers ahead today, vowing to continue to campaign for the repeal of all anti-union laws. In 1966, seafarers were witch-hunted back to work by the Wilson Labour government who used ‘red scare’ tactics to get the NUS executive to accept a compromise deal.

The Socialist Labour League (SLL), forerunner of the Workers Revolutionary Party, published a pamphlet in the aftermath of the strike, warning: ‘The anti-union legislation of the Labour government soon after the end of the seamen’s strike, points to the intervention of the state in every single industrial dispute.

‘The wage freeze that followed showed that no worker can escape from the political implications of industrial struggles. The seamen’s strike became a political strike.

‘It was defeated because the seamen’s leaders did not put up a political fight.

‘Only by fighting for political leadership, by raising continually the question of the power of the state, are workers going to be able to triumph in the many similar struggles that must now follow.’

The SLL said that the development of rank and file movements to challenge the trade union bureaucracy was important but not sufficient in itself. The most important lesson of the strike was it was against the Labour government and it required a revolutionary strategy and leadership to defeat the TUC stab in the back and win, the SLL stressed.

The Labour government continued to draw up its own anti-union laws ‘In Place of Strife’ but were removed in the 1970 general election which saw Edward Heath returned who brought in his own anti-union laws, complete with industrial courts, which made strikes illegal and led to the jailing of five dockers in Pentonville prison.

A mass movement of workers forced the TUC to threaten a 24-hour general strike and this was enough to achieve the release of the dockers. The miners then entered the struggle and their strike actions pushed Heath to the point when he decided he would have an election over who ruled the country – the government or the trade unions.

He lost the 1974 election, another Wilson government was formed and the only way a workers revolution could be prevented was by Labour scrapping all of Heath’s anti-union laws. The big lesson for today is that when trade unions are threatened by the state they have to fight it and be prepared to overthrow it if they are to maintain their rights.