AROUND 600 Frito-Lay workers in Topeka, Kansas, have been on strike for over three weeks, since Monday 5th July, against low pay and forced overtime and 84-hour working weeks.

The strike was said to have started after an employee collapsed and died on the factory floor and instead of stopping the line, co-workers reportedly had to help remove the body so another person could step in.

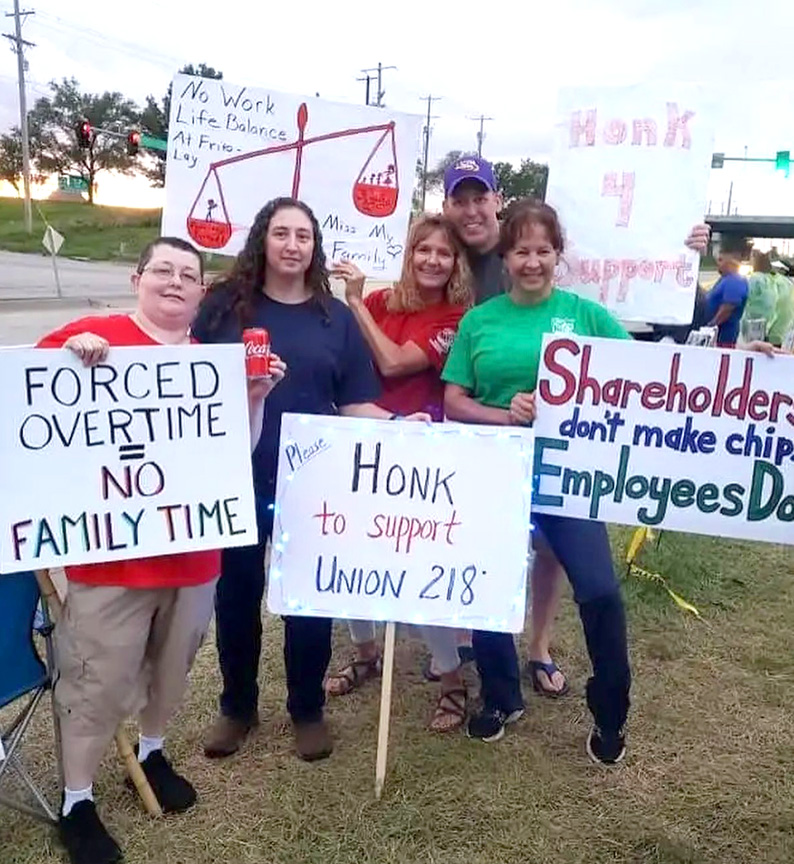

Members of the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union (BCTGM) Local 218 voted 353 to 30 to approve a strike.

Frito-Lay is a division of PepsiCo and has been a major contributor to the company’s bottom line, earning $1.2 billion in profits on $4.2 billion in revenue in the first quarter.

Last year, the division was responsible for over half of PepsiCo’s operating profits, with profits of $5.3 billion on $18.2 billion in revenue.

PepsiCo also owns brands including Mountain Dew, Quaker Oats, Gatorade, Tropicana, and Aquafina.

Topeka is one of the largest of Frito-Lay’s 30 US manufacturing facilities; most are non-union.

The 850 workers there make, package, and ship nearly every type of Frito-Lay snack: Lays potato chips, Tostitos, Cheetos, Sun Chips, Fritos, every flavour of Dorito, and more. Six hundred are members of Local 218 (Kansas is a right-to-work state).

Some workers have been forced to work 12-hour shifts, seven days a week, for weeks on end due to short staffing. They want to see that change.

‘Nobody I know loves Frito-Lay enough that they want to live there,’ said Monk Drapeaux-Stewart, a box drop technician, responsible for keeping the plant’s machines supplied with cardboard.

‘We want to go home and see our families. We want to have our weekends off. We want to work the time that we agreed to work – and hopefully not much more than that.’

The last several contracts have featured lump sum bonuses most years, leaving wage rates stagnant for most classifications.

Drapeaux-Stewart said he’s only got a 77-cent increase over the last 12 years.

‘Fifteen, 20 years ago Frito-Lay had a really good reputation – all you need is a high school diploma and you’ve got this job with good pay and benefits,’ said Drapeaux-Stewart, who started working at the facility 16 years ago. ‘But slowly all of that has been whittled away.’

That’s made it difficult to maintain workers and led to the mountains of forced overtime.

‘Conditions are really just deteriorating as each contract rolls by,’ said Cheri Renfro, an operator in the Geographic Enterprise Solutions department, where workers fulfill orders for smaller mom-and-pop shops and gas stations.

Renfro estimated that the company brought in more than 350 employees in the last year and lost the same amount. ‘You have to wonder as a company why wouldn’t you question that – say, “Hey, what’s going on?”.’

On 5th June, workers voted down the latest contract offer from the company, which included a two per cent wage increase this year and a 60-hour-a-week cap on the amount of hours a worker can be forced to work.

The wages weren’t enough and the overtime cap would have meant more senior workers being forced in on weekends, workers say.

Other issues fuelling workers’ anger include safety, a punitive attendance policy, and pressure from inexperienced supervisors competing for promotions.

‘This storm has been brewing for years,’ Renfro wrote in a letter to the Topeka Capital-Journal, in which she outlined examples of the plant’s ‘toxic work environment,’ including management keeping the line going after a worker collapsed and died and refusing bereavement leave for a worker whose father died during the Covid lockdown, since there was no funeral.

‘In the past people were afraid to go on strike – you keep hoping every contract is gonna be better,’ said Renfro. ‘But as time has gone on the company has proven they are not gonna get better and they are not gonna work with us.’

The plant never slowed down during the pandemic, workers said.

Instead, production increased, as people ate at home more and bought more comfort foods like chips.

‘I’ve learned that when something’s hitting Americans beneath the belt, the two main items that never suffer are snack foods and alcohol,’ said Benaka, who retired from the plant in 2017 after 37 years.

Workers were at one point given an extra $20 a day to work during the pandemic, up to $100 a week – but that only lasted a few weeks.

‘I don’t know if they were afraid we were gonna get used to the higher wage,’ said Renfro.

Production at the plant fluctuates seasonally – it’s busier in the summer and around big holidays and the Super Bowl.

Workers are used to overtime during those periods. But recently the overtime has become constant. ‘Now we’ve having overtime when we shouldn’t be,’ said Renfro – and a lot more of it.

Renfro said she worked 73 hours during the week leading up the Fourth of July, and then worked from 3am until 3pm on the holiday. ‘I went to sleep – didn’t even hear the fireworks, I was so tired.

‘I’ve had to miss going to so many holidays because I’m getting forced,’ said Renfro. ‘I’ve had to call my mom and tell her I couldn’t make it. I don’t want to miss those moments anymore. I’m done with giving everything to Frito-Lay – my time, my holidays.’

One of the most hated forms of forced overtime at the plant is being forced to work a ‘suicide.’ That’s when the company makes a worker stay four hours on top of their eight-hour shift, and then forces them in four hours early before their next shift – leaving them only eight hours off.

The company has set up a parking lot a mile from the plant. It’s running coach buses from the lot every 15 minutes to shuttle in temporary workers and out-of-state scabs.

But strikers suspect that the buses are a ruse. ‘Most of these buses are completely empty, or have one to three people, not counting the driver,’ said Drapeaux-Stewart. ‘It’s psychological warfare – they’re trying to demoralise and dispirit the men and women of the union in the hopes we’ll come grovelling back for whatever crumbs they offer us.’

Strikers are also monitoring the facility’s smokestacks to get a sense of the strike’s impact. ‘There’s been no smoke, no steam, no nothing, no sign of production at all,’ said Drapeaux-Stewart.

‘Usually there’s always an odour coming out of Frito-Lay, but it’s been smelling really good outside,’ said Renfro.

Local supporters have been donating food and water to the picket line. Some local restaurants have said they will stop serving Pepsi products. A local magazine, 785, has set up a fund to help strikers pay their water bills.

‘I’m really amazed at the community support,’ said Renfro. ‘It makes you proud to be a part of this community.’

‘It’s scary but it’s exciting,’ said Drapeaux-Stewart. ‘I have so much hope for this strike that we will finally get what we’ve needed – the guarantee of getting to see our families, and earning a living wage to support those families.’

It is more than 90 degrees fahrenheit outside the Frito-Lay plant in Topeka, but standing in the picket line feels cool compared to inside the warehouse, where at 7am most days temperatures are already peaking over 100, said Reyna Corbus.

Corbus is one of the more than 500 workers on strike at the plant demanding higher wages and more limited hours.

Since July 5, workers have gathered across from the warehouse entrance with signs asking for public support and chastising Frito-Lay.

Last week, Corbus came equipped with a hand-painted sign made by her daughter depicting a boot stomping on workers attempting to speak up.

Many of the employees of this plant describe feeling like the image on that sign – silenced or stepped on by Frito-Lay.

Working in strenuous and scorching conditions without proper compensation, as she has done for 20 years, is unsustainable, Corbus said.

‘We need to start to be treated like humans,’ Corbus said. ‘We give our life to the company because we have spent so many years away from the family. We already talked to the company so many times and they just don’t want to give us anything.’

Paul Klemme, chief steward of Local 218 of the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers Union, said many departments have not seen more than 20- to 40-cent raises in the past six to eight years, which made Frito-Lay’s offer so offensive.

‘This isn’t a greed issue,’ Klemme said. ‘The last 10 years Frito-Lay has started to treat their employees worse and worse and worse, so it’s finally snapped on this contract.’