APRIL 21 saw the 175th anniversary of the Grand Demonstration of 1834 when over 100,000 marched from Copenhagen Fields in London to Parliament to demand the release of the Tolpuddle Martyrs.

This was the first mass trade union protest, a key moment in the determined fight to obtain the release of six Dorset farmworkers who had been sentenced to seven years transportation to the penal colonies in Australia for forming a union to defend their livelihoods.

To mark the occasion there was a rare, one-night only showing of Bill Douglas’s classic 1986 film ‘Comrades’ at the ‘Screen on the Green’, Islington.

This epic of British film making starts with a scene of the violent suppression of the 1830s machine-breaking by agricultural workers out to preserve their jobs, which is observed by an itinerant lanternist who travels the countryside entertaining with his projector.

The film captures the beauty of the Dorsetshire countryside in all its stunning splendour; while at the same time revealing the back-breaking work to be done across the seasons. The village scenes, in contrast to those often seen in present day costume dramas, reveal the economic and social reality in the countryside – an impoverished daily existence forced upon the people by the landowners in their continual attempts to increase their profits.

In scenes of everyday family life, the camera portrays the farmworkers with lingering close-ups creating the atmosphere of the period, and enabling you get time to discern feelings and take in words; a deep respect for their lives is obvious.

Douglas slowly brings out how their changing conditions force the principled, determined men to seek out a way to protect themselves and their families; they are slow to act but then stubbornly determined.

The farm labourers being all too aware that their wages don’t match those in the neighbourhood, approach the landowner for a rise which is promised, but the next day they find their wages have been cut! This was the last straw and George Loveless decides to seek advice on how to form a union: to ‘preserve ourselves, our wives, and our children, from utter degradation and starvation’.

The film shows the making of their branch banner with its image of a skeleton and the legend: ‘Remember thine end’, and a clandestine, dead of night meeting where new members are inducted into their ‘Tolpuddle Lodge of the Agricultural Labourers Friendly Society’. The banner is on the wall and revealed to the accepted members who have been vouched for and who have sworn never to disclose what they hear. They are told: ‘Brothers, mark you well this emblem that you see. It’s an emblem of man’s destiny. Should you ever prove deceitful – Remember thine end!’

On hearing that the farmworkers had formed a union, the landowners were beside themselves and conspired to break it. The six, George Loveless, James Loveless, James Brine, James Hammett, Thomas Stanfield and John Stanfield, were arrested on February 24 1834. Although Trade Unions had been declared legal, the men were charged under the 1797 Mutiny Act, and in court found guilty of administering illegal oaths.

In chains and on his way to the prison ship, Loveless drops a crumpled paper which is picked up by a beggar; on it are the words:

‘God is our guide! from field, from wave,

From plough, from anvil, and from loom;

We come, our country’s rights to save,

And speak a tyrant faction’s doom:

We raise the watchword liberty; We will, we will, we will be free!’

Their seven-year sentence of transportation to the penal colonies of Australia and Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania), roused workers the length and breadth of the country in a campaign which eventually won free pardons and the men’s return to England.

Douglas shows the dire conditions that the Tolpuddle Martyrs had to endure in Australia, how they were hired out as slave labourers to owners of estates and the government administration, how if they ran away a deadly sentence of forced penal labour awaited them.

Again, we see visually superb portrayals of dramatic landscapes combined with toil, this time that of prisoners, and the same viciousness of a ruling aristocratic government. The film ends showing a packed meeting celebrating the success of the freedom campaign, a landmark in the history of trade unionism.

The film is also remarkable in that throughout both parts Douglas uses the device of the lanternist, who connects different parts of the story, to deliver what amounts to a history of the development of pre-cinematic entertainment; from time to time at lighter moments, at fetes and in houses, people gather and see what could be called pre-film shows, where they watch images from a variety of different types of projectors.

Douglas’s massive collection of artefacts and literature on the subject was donated after his death in 1991 to Exeter University where it forms the basis of the collection at The Bill Douglas Centre for the History of Cinema and Popular Culture.

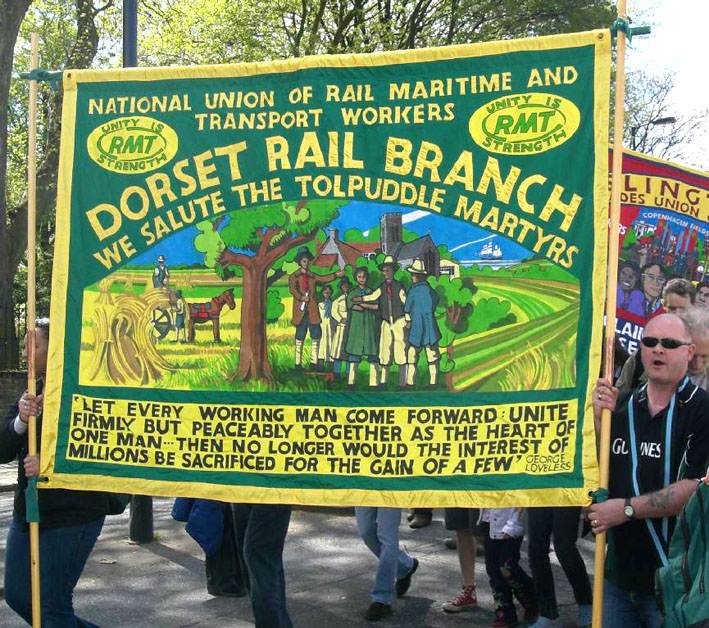

Last Saturday, April 25, the Grand Demonstration of trade unionists for the release of the Tolpuddle Martyrs was celebrated with a march and rally in Islington.

Before setting off to a rally in Edward Square, several hundred trade unionists watched children from Hungerford Primary School give a stirring enactment of Dorsetshire agricultural labourers demanding their rights, and saw Frances O’Grady, TUC deputy General Secretary, unveil a commemorative plaque on the Caledonian Park clock tower, on the site of the old Copenhagen Fields where the Grand Demonstration gathered.

Led by the lively Cuban Solidarity Salsa Band, they marched in bright sunshine down the Caledonian Road to a rally.

Megan Dobney, SERTUC regional secretary, welcomed the marchers and said that the trade unions were holding high the flame that was lit 175 years ago, reminding everyone that ‘we are here to celebrate the past, not dwell on it.’

Sean Vernell, UCU national executive, certainly wasn’t dwelling on the past when he drew the, by now thousand-strong, crowd’s attention to the desperate struggle going on in Further Education against mass job cuts and course closures. He aslked for support on their London demonstration on May 23.

The crowd basked in the sunshine, talked politics and generally enjoyed themselves while entertainment was provided by the Raised Voices Street Choir, singer, songwriter and playwright ‘Tolpuddle Man’ Graham Moore, plus Martin Carthy, Leon Rosselson, Billy Bragg, and the Musical Flying Squad with its young backing singers from Copenhagen and Blessed Sacrament schools.