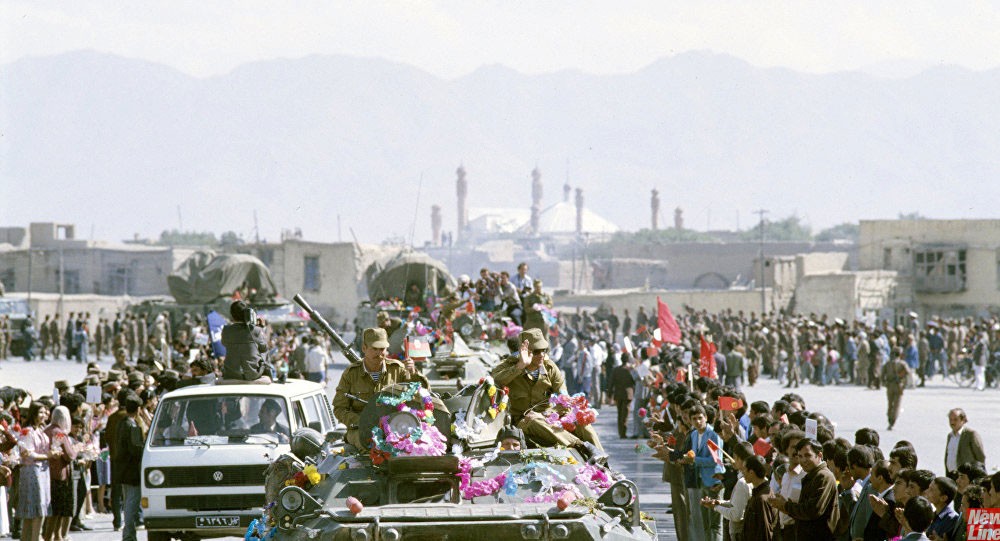

THE 15th of February marked the 30th anniversary of the pullout of Soviet troops from the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. The Soviet-Afghan War lasted from December 1979 to February 1989, with troops from the Soviet Army and its allied Afghan government forces fighting against the Mujahideen, supported by the United States and its allies.

In an exclusive interview with Sputnik, Colonel-General, Hero of the Soviet Union Boris Gromov, has spoken about how the decision on the need to withdraw troops was made, how the 40th army command pulled out from the territory of Afghanistan, how difficult it was to carry out this operation, as well as what unforeseen situations arose during the withdrawal period. He has also spoken about the reasons why American diplomats reached out to him after the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks.

Sputnik: You spent five and a half years in Afghanistan. What was the most difficult during your stay in Afghanistan?

Boris Gromov: The beginning of my stay was the most difficult for me. I flew there in January 1980, and in March hostilities began. At that time, I had graduated from the Academy (the Frunze Military Academy in Moscow) and, as I thought, was prepared for combat operations.

At first, I was a colonel, chief of staff of the 108th division in Kabul. The attacks occurred even before March, but we could not respond because that had been strictly forbidden.

In March, I began to act as the head of combat actions near Kabul. Those first combat actions were the most difficult period that remained in my memory. Since then, I have made a number of practical conclusions: do not go into a battle without understanding the situation.

Sputnik: What surprised or shocked you when you were in Afghanistan?

Boris Gromov: The first moment that shocked me occurred in February 1980. I was then the chief of staff of the 108th division that was at that time deployed on the northern outskirts of Kabul, which was later transferred to Bagram. We held meetings of the division leaders, as it was done in peacetime in the USSR. After one such meeting, a command was given to return to their locations.

An hour later, a report was received that on the road from Kabul to Bagram, where the engineer battalion was located, a car was fired at and a lieutenant colonel, the commander of the engineering battalion, was killed. Not only did he and his driver die, the enemy forces ripped him apart with knives, cut off his ears, gouged out his eyes, and abused the corpses.

I was there, I was terribly shocked. We were raised in a peaceful life and believed that this was impossible, but it turned out that it was possible. Throughout the nine years of the Soviet campaign in Afghanistan, such cases were constantly repeated.

Sputnik: What is your opinion about ordinary Afghans?

Boris Gromov: The Afghans, who were not part of any Mujahideen detachments, were sincere and very good people. They lived very poorly, but they were wise, humane, they had a friendly attitude toward people, including shuravi (the Persian term for the word “Soviet”). Maybe they did not fall on our necks, but they had their own code of honour, behaviour.

They treated us, the Soviet people, very well, and we treated them the same way. We helped them a lot, we built things, supplied food. They appreciated it.

Sputnik: How did you assess the chances of the USSR for success at the beginning and how did your opinion changed during the war? How did you come to realise that there was no military solution to the Afghan problem?

Boris Gromov: I was in Afghanistan three times. At first, I could not judge the correctness of the decision. A year and a half later, when I got to know practically the whole of Afghanistan and went everywhere, I realised that the idea that they wanted to put into practice was not feasible.

At that time, both the United States and NATO did everything to drag the USSR into Afghanistan. I also became convinced of this during meetings with the commander-in-chief of NATO’s southern forces. They never made a secret of it.

In my opinion, when deciding on the deployment of troops and international assistance to Afghanistan by the leadership of the USSR, apparently, not everything was taken into account, or there were other moments that we do not know about. Now it is obvious to me that the deployment of troops was prepared thoughtlessly.

During the first two years of the presence of our troops for many officers and the leadership of the 40th Army – and the Ministry of Defence was always against the introduction of troops – it became obvious that measures should be taken to withdraw from Afghanistan. There existed no task as such for the 40th Army.

The only mission was to maintain a calm situation in Afghanistan in order to avoid the penetration of military conflicts from outside. The entry of troops into Afghanistan was ahead of the actions of the Americans, which can be considered the only advantage of the entry of Soviet troops into the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA).

This issue could have been resolved differently, for example, by not sending the 140,000 contingent of Soviet troops but to limit ourselves to the one that had already been introduced – 30,000. These forces would have been enough to maintain stability and the authorities in the main areas.

Afghanistan could not be abandoned, it was necessary to help but it had to be done differently, politically and economically. In particular, if there were problems and military conflicts with the Pakistani side, special detachments could have been sent there. Moscow had them – Special Forces, GRU.

At the 40th Army, there was a GRU reconnaissance centre, whose forces covered the entire territory of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran.

Sputnik: How was the decision to withdraw the troops taken?

Boris Gromov: Starting from 1983, the command of the 40th Army deliberately insisted on the decision to withdraw troops through the Ministry of Defence, through the Soviet Embassy, through all those who made such decisions.

We prepared the documents and sent them to the Politburo on Old Square in Moscow. We seriously began to consider the decision on the withdrawal of troops in 1985, when it became clear that the issue could not be resolved by force.

The decision was finally made in Geneva, the so-called “Geneva Agreement” was signed by Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The USSR and the United States acted as guarantors. The agreement defined the deadlines for the withdrawal of the troops: the beginning of the withdrawal was scheduled for 15 May 1988, and the end of the withdrawal was for 15 February 1989.

The only thing it did not specify was the order for the withdrawal of troops because that was determined by the 40th Army command. It was the command of the 40th Army that insisted on the withdrawal of troops since all the tasks that depended on us in Afghanistan had been resolved.

We showed everyone, including the Americans, that while the 40th Army was in Afghanistan, it was useless to go in there and fight with the USSR. The Americans are still talking about it now. However, the United States did everything in their power to detain the Soviet troops in Afghanistan for as long as possible.

Sputnik: It has been argued that the USSR was defeated in this war, but what do you think?

Boris Gromov: After the withdrawal of troops, those who have no idea what Afghanistan is, who have not fought there, often tell tales that the USSR and the 40th Army were defeated in Afghanistan. There were no tasks that the 40th Army could not perform.

It was a very powerful army. There can be no talk of a defeat. The forces that were present there were simply incomparable.

On the one hand, there were us, and on the other, those who acted on the orders of the United States. The Americans acted undercover. The former head of the CIA wrote about this in his memoirs.

The US did everything using Pakistanis and Afghans as proxies, who were on the Pakistan side. And most importantly, the 40th Army in Afghanistan has never and from no one received the task of achieving a military victory.

When they say that our army suffered a defeat there, these people should be called “storytellers” …

Sputnik: Could you please tell in more detail about how the preparations for the withdrawal were conducted and how the pullout itself took place? How difficult was it to carry out the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan from a technical and tactical point of view?

Boris Gromov: The Americans did everything to ensure that the pullout either did not take place or, if it did, with huge losses for us. We were preparing seriously, used everything that was possible: both space and other means of intelligence that existed at that time. We knew everything about every kilometre of Afghanistan. The withdrawal of troops was carried out in two directions: the western – along the Iranian border, and the central – through the south, southwest to Kabul, through Salang to Termez and to Kushka. We set up and maintained contacts with all the leaders of the Seven Party Alliance*, with parties that were in Pakistan, but whose armed units were located on the territory of Afghanistan.

* The Seven Party Mujahideen Alliance or Peshawar Seven (official name is Islamic Unity of Afghanistan Mujahideen) is a military-political union of the leaders of the Afghan Mujahideen during the war of 1979-1989

Sputnik: It’s known that an agreement was reached with Massoud (Afghan field commander, one of the key figures leading the fight against Soviet troops in the northeast of the country in the Panjshir valley area — Sputnik note) that he would allow the convoy of Soviet troops through the Salang Pass without fighting. How was the agreement reached? What was your relationship with Ahmad Shah? You met him. How do you remember him?

Boris Gromov: He was a worthy man, despite the fact that he was one of our main opponents. Ahmad Shah had a clear understanding of everything. People that lived in the Panjshir Valley loved him very much. Massoud was a very responsible person. If he made a promise, you could be 100 per cent sure that he would keep it. We met with him once before the withdrawal. This happened in May 1988. Before we met, we wrote letters to each other, sending them through intelligence officers. We agreed upon everything, settled all the problems, and organised an engagement so that nothing unpredictable would happen. We had passwords, besides that, we coded our communication so that no one else could speak on behalf of Ahmad Shah.

The last time we agreed on the place – it was not far from the 177th regiment’s position, before entering the foothills where the mountainous part of the road to Salang begins. The road to the right led to Panjshir, and the main road went straight ahead: Kabul – Salang Pass – Turgundi. We met at a crossroads without guards. We talked about five minutes, reaffirmed the agreement. We often communicated after that. And then they set us up. Shevardnadze insisted that before the troops’ withdrawal, just when our last two columns had to cross Salang, we had to carry out a powerful strike on Ahmad Shah, which was done. Even though our strike was launched, Massoud did not strike back.

Sputnik: There is information that the strike hit empty canyons. Is that so?

Boris Gromov: The strike hit targets provided by Moscow, by the GRU. The targets were demanded by Gorbachev, this was told to the defence minister. Maybe, our guys somehow warned Ahmad Shah that we had to conduct the airstrike. Targets were designated along the road, where Massoud’s people were. Some 90 per cent of them left. They had their own agents, and we also warned them. Airstrikes were also conducted deeper into the territory — east and west of Salang.

More airstrikes were conducted by strategic aviation, from the USSR. But we were firmly opposed to those strikes. We phoned Moscow and said that the 40th Army will not take part in this. In fact, breached the rules of subordination. We explained that if these strikes were to happen and succeed, the forces that remained near the beginning of the mountain pass to Salang will never leave Afghanistan. If the Mujahideen retaliated, that would have been a tragedy.

Sputnik: What were your first thoughts and words when the withdrawal concluded?

Boris Gromov: I said to myself something along the lines of “thank God it’s all over”. I didn’t have the strength to talk. I also had words that were better left unspoken.

Sputnik: Have you had an urge to go to Afghanistan? Have you been there since the withdrawal?

Boris Gromov: I do not have such an urge. I have been in almost every corner of Afghanistan. I don’t exactly have good memories connected to those places.

Sputnik: Did the US ask for your advice on fighting in Afghanistan, considering your experience?

Boris Gromov: Of course, following the 9/11 attack, I was contacted by the US Embassy and NATO. This was even before the US intervention. I described everything in grim colours. I tried to explain to them that they would have a hard time there, and that they were making a mistake by getting into there. But they went in there, and they have stayed there for 18 years already.

Sputnik: Have you been contacted now, considering Trump’s recent announcement of the withdrawal of half the foreign forces from Afghanistan?

Boris Gromov: No, not these days. (The US) won’t be able to repeat our withdrawal experience because they have no ground forces in Afghanistan. We withdrew by two ground routes. If they withdraw, they will do it by air. If they try a ground withdrawal, the Afghans won’t forgive them, because (Afghans) don’t like Americans; so (the US) will withdraw by air, and this is a completely different

matter.